"The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a Heav'n of Hell, a Hell of Heav'n."—John Milton, Paradise Lost

As I approached mile 19 of the Run for the Red Pocono Marathon feeling exhausted, a voice whispered that this race was not meant to be. I was pushing for a 3:30, a time I'd been chasing for five years. The temperature was cool. The Pennsylvania course barreled downhill. Prime personal-best conditions—save for the words in my head. You've done your best, the voice said in a calm, caring tone. I inhaled, pretending, as I had many times before, that I wouldn't listen. But when it said—It's okay to slow down—I conceded, dropping to a shuffle, finishing the race far off my goal time.

For years, I'd clung to the idea that better physical training would propel me through these tough spots. But repeatedly, after solid 16-week training programs filled with long runs and race-pace miles, I succumbed to doubts. After the Poconos race, I finally admitted that I didn't need another 20-miler, I needed to learn to talk back. Science has confirmed that performance at the end of an endurance event has as much to do with psychology as physiology. Thinking is a behavior, and I set out to change mine.

Plenty of runners have boosted their mental toughness using visualization and mantras. I experimented with one—Yes, you can!—during a 10-K and felt silly, not motivated. In theory, mental training made perfect sense: Alter your thinking and you improve your results. But how, exactly, does one rewire thoughts?

So when I began training for my next race, the Napa Valley Marathon, I called Dean Hebert, M.Ed., a certified mental-game coach in Arizona and a former 2:36 marathoner who specializes in working with runners. In our test-the-waters call, I told him about my habit of slowing in the final miles. "No one expects endurance to come naturally," he said, "but people think mental toughness does. It's a big myth. You do not need more willpower. You need to train the brain like you train the body." This means practicing mental skills throughout training, not randomly tossing in a mantra midrace. Mental skills, like physical strength, develop over time and with consistency.

Every sports psychologist has his own process. Hebert's mimicked a coach's: initial assessment, followed by a clear, written action plan to use with a training plan, plus biweekly e-mails and phone calls. Completing the intake form was harmless, but his summary of it was hard reading: "confidence is fragile," "fears she is not as tough as she thinks," and "doesn't really believe she can."

In short, I was a classic head case: a negative-thinking, results-oriented runner. Mentally tough athletes are positive thinkers and process-oriented. "If you focus on results, you take yourself out of the now," says Stan Beecham, Ph.D., sports psychologist for two elite running groups, McMillanElite and Zap Fitness. "And it's the now that allows for the results later." He compares it to football: In the pregame huddle, a good coach won't tell his team to go out and win, he'll say, go out and pass well, tackle hard. Those are the steps that lead to scoring, and winning. If runners do the same, the results will come.

Being positive is just as critical. In a recent study, pessimism ranked as runners' top mental roadblock. Negativity, whether it's worry or doubt, often leads to self-defeating behaviors including slowing down, cutting a workout short, or dropping out of a race. "It is the self-fulfilling prophecy," says Cindra S. Kamphoff, Ph.D., director of the Center for Sport and Performance Psychology at Minnesota State University. Mentally strong runners don't go there. They use their thoughts and their training to feed a belief in themselves. This became my goal.

Focal Points

In order for mental training to be effective, it must be individual, so my next task was to set personal process goals and determine a focus tool. Process goals are the specific physical and mental steps that lead to a performance goal, like setting a PR or finishing a race without walking. They should be measurable and address your weaknesses: Practice five minutes of visualization daily (if you struggle seeing yourself succeed); do weekly fast-finish runs (if you slow in the final miles of a race); follow a training program (if you tend to skip workouts).

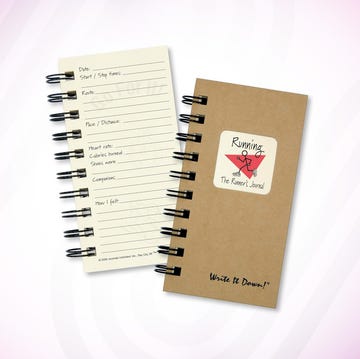

I already did fast-finish workouts, but I sometimes cut them short or let myself slow—same as I'd done in my marathons. "Yes!" Hebert said. "That's it. Your physical training is your mental training." This is a key tenet in sports psychology. What you do in training, you will do on race day. So sticking to my mileage and pacesbecame a process goal. Hebert added a second: Score my workouts (8 out of 10 for completing eight miles of a 10-mile run). Most sports psychologists employ some form of record keeping. Beecham's athletes mark workouts as wins or losses. The process strips a single workout of power, showing you that you can have a lousy run (a "loss") and still have a strong training week (filled with "wins").

Next was selecting a focus tool—a word, phrase, or action that mutes destructive chatter and keeps you in the moment. "Some people thrive off discomfort, thinking, I'm tough; I can push through this," Hebert says. "Others benefit from competition—visualizing reeling in runners helps them put pain aside. You have to learn what works for you."

This can take time. One of Hebert's runners started listening to her breathing, only to realize the sound of heaving lungs intensified her anxiety. Reflect on what calms, motivates, or engages you and start there, Hebert suggests.

Craving silence, I opted to focus on my footfalls and elbows. The first time I used my tools—during a 10-miler when I felt tired and grumpy—the sluggishness lifted. At the track, I listened to my feet and concentrated on swinging my elbows smoothly when the burn of 800s got to be too much (or I thought it was too much. Semantics are important. It's not splitting hairs, the psychologists say, it's changing what you believe).

Day after day, workout after workout, every time I caught myself dwelling on fatigue or launching into a conversation on why I should turn around, I instead concentrated on my feet and elbows. I held pace. Even blew past a split or two. Here's what surprised me: Hardwiring the mind is as formulaic as anything else. If you take action, results follow. Do speedwork; get faster. Eat less; lose weight. Stop negative thinking; punch through pain.

Unexpected things began to happen. My motivation skyrocketed. I trained better, did drills, more recovery runs, core work. Hebert wasn't surprised. Strong workouts breed confidence, he'd said, and conversely, belief in your ability can produce strong workouts.

I quickly came to love mental training. All the positivity—or at least the lack of negativity—proved seductive and I hungered for it. I started using form cues on every run. Awareness built. One morning while ruminating on all I'd rather do than run, I pictured the golden mountains I'd see on the trail. By the time I was out the door, I felt like running.

Critical Thinking

Still, I couldn't shake my preoccupation with time. Six weeks into my training, I worried that a string of 8:08 miles wouldn't add up to my goal time (I needed to run 8s).

"You don't control if you run 3:30," Hebert said on our check-in call. This statement came as a shock and delivered a bit of panic. "You only control the steps that improve your chances of hitting that time, from how well you train to whether you take in fluids on race day."

"In a race, what do you think when you hit 7:45?" Hebert asked.

"I worry that I will die."

"8:15?"

"I doubt I'll reach my goal."

"Notice they're both negative?"

Ah.

"Why not look at numbers as feedback?" he said. "7:45—oh, I'm on today. I better pull back a bit. 8:15—good. Just a little more."

Reframing is key. When you seek to find the positive, information becomes useful. What did 8:08s tell me? That marathon pace would require more effort. This was good to know.

That night, I went through my log marking each workout a win or loss—Beecham's scoring method. "If you think every workout has to be good or every split exact, you waste energy recovering from the disappointment," he said. "But if you see a few poor workouts or even a bad race as part of the process, you can move on." When I saw the 8:08 run in my log, another sports psychology tenet took root: A strong inner game can come only when you're honest with yourself. The truth was I could have pushed harder, I just hadn't felt like it. I marked the workout a "loss," for lack of effort. Admitting this was liberating.

Head Strong

Eight weeks before race day, I was five miles into a seven-mile tempo run when a lightning rod of pain passed through my chest. Not sure I can hold this. I locked into elbows-feet, and in the quiet that ensued, the voice returned: Yes, you can. The words surprised me. I held on, hitting mile six a bit fast (7:26), then mile seven in a fatigue-bashing 7:12. I called Hebert and told him I'd realized that just because I felt crappy didn't mean I was going to fall apart.

"Write that down," he said, "because that's one of the best revelations you'll ever have. If you understand that you can run well when tired, you change your performance drastically."

In sport, fatigue is highly subjective. The brain processes physical cues (chemical and electrical signals from the muscles) and environmental information (how we expect to feel) and concludes, Hey, we're done here. But years of research shows that the mind can override the body—that fatigue, more often than not, is a product of perception rather than true physiological depletion. "Fatigue is simply a sign that you need to put your mind on something positive," Kamphoff says.

In a 2012 study, researchers pitted cyclists against a computerized competitor during two trials. For one, the cyclists were told the opponent was riding at each cyclist's personal best pace, when, in fact, the rival was going faster. In another test, they were told their competitor was speedier. When the cyclists thought they were facing a faster foe, they couldn't keep up—they doubted they could beat someone quicker. But when they thought they were evenly matched, they rose to the challenge. The fitness must be there, but the mind decides whether you access it.

During the first half of my training, the benefits of mental training had become apparent, but it wasn't until that seven-mile tempo run that I truly believed in them. It was like the magic of speedwork; you know intervals can make you faster, but when they do, it feels like a small miracle. Mental training was no different.

Powered by a sense of confidence, the second half of my training led to some of the best workouts I'd run in 20 years. My inner dialogue became positive. I heard Hebert's voice—refocus, find the good in every run—and experimented with various power words: calm, strong. For the taper, Hebert assigned three tasks: read my training log to see how much work I'd done; visualize punching through pain; finish every run with a half-mile hard effort, no letup, not an inch short.

Still, doubt remained. What if I went out too fast? What if I really couldn't hold pace? What if I just wasn't tough enough? But my mental skills also kept progressing. Two weeks out, during the last few miles of a tune-up 10-K, my self-talk was this: You have more. Make it burn. Me, seeking pain? Like I said, a miracle. "A mentally strong elite doesn't just know she can win," Beecham says, "she knows that winning will be hard."

Pressure Day

At the start of the Napa Valley Marathon, 1,800 of us moved down the misty valley. Mile one: 7:54. Perfect. I fell into an easy rhythm, taking in the green hills, the vineyards, the soothing sound of feet on pavement. But then I started looking for mile markers. I worried I was too focused on the numbers, too eager for the reassurance of a perfect split. Then mile 10 came and went, as did 11, 12, all on pace, yet still the anxiety built. I slipped into feet-elbows, but the calm didn't come.

At mile 15, panic threatened. I needed to know: Would I do this? Mile 16 came in at 8:23. Just as I was leaning over the cliff, the voice spoke: This mile. I smiled, and responded. That's right, all I control is this mile. Mile 17: 7:33. Too much. Just feedback. I arrived at mile 20 13 seconds shy of goal pace. A bit more. 7:51. Hold. But the seconds crept on, 8:06, 8:12. C'mon. I rounded the corner to the finish, passed my husband, who looked at his watch, both of us wondering if I'd made it. I had, by a hair: 3:30:57.

Every runner's mental-toughness journey varies. One of Hebert's athletes refined his ability to focus in training, which led to the revelation that he could catch runners in front of him. One of Beecham's learned to untie her self-worth from her performance. Others have found that simply becoming more aware of their not-going-to-run excuses helped them develop the discipline to get out the door. For me, the process changed the tone of my self-talk, enabling me to tap strength I feared wasn't there.

In our postrace analysis, I asked Hebert about my lack of focus and confidence in the middle miles. "The longer you've thought a certain way, the deeper the mental grooves," he said. "It takes time to change those patterns."

Over the next year, I continued scoring workouts and using focus tools. I smashed my half-marathon personal best and came dangerously close to my 10-K PR, something I hadn't done in nearly a decade. In a recent half-marathon, I ticked off runner after runner in the final miles, cruising to another personal best. The voice and me shouting together—You've got this!—all the way to the finish.