After a race or hard workout, our bodies can be pretty out of whack. Cortisol, a hormone that’s released when we’re under duress, floods our systems. And our beat-up muscles, replete with micro-tears, trigger an inflammatory response that makes us feel stiff and sore.

Although it sounds awful, this stress response enables our bodies to adapt and become stronger. But if cortisol and inflammation linger, and broken-down muscles don’t regenerate quickly, trouble is on the way—in the form of decreased performance, injury, and illness.

To promote a swift return to normal, most runners turn to such traditional recovery techniques as icing, foam rolling, and massage. New science, however, is uncovering ways that we can use our minds to restore our bodies. The bonus? Each is less painful than an ice bath.

Awesome Experiences in Nature

New research is beginning to reveal that the benefits of nature go far beyond the aesthetic. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a molecule that encourages inflammation throughout the body. It turns out that awesome experiences in nature—that stir feelings of vastness, self-diminishment, and beauty—may be linked to lower IL-6.

Researchers from University of California, Berkeley, found that more than any other emotion, awe is linked to lower IL-6. “Awe has a strong negative relationship to a marker of inflammation, a phenomenon that seems like it’d be quite beneficial to runners,” says study author Jennifer Stellar, Ph.D. Although more research is needed to zero in on why awe has these effects, Stellar believes that “experiencing awe gives us a greater sense of well-being, makes us feel more connected to the universe and more humble.” These feelings, she says, “may reduce stress, lessening inflammation.”

“The day after a race or hard workout, consider a walk in the woods or an easy run at sunrise or sunset,” Stellar says. Not only does light movement aid muscular recovery by stimulating blood-flow and flushing out the waste products of muscle breakdown, but simply being in nature could reduce lingering inflammation. “Just be sure to disconnect and really take in your surroundings,” Stellar says. Even a run in the most pristine place won’t induce awe if you’re glued to your phone.

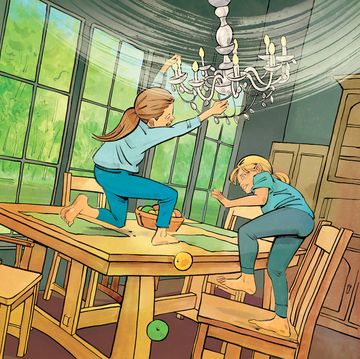

Social Recovery

Research published in Physiology & Behavior reports that the ratio of testosterone to cortisol—which acts as a good indicator of systemic recovery (the higher, the better)—was higher in athletes who watched postgame videos in a social environment with friends than in athletes who watched postgame videos in a neutral environment with strangers. What’s more, the “social group” performed better in competition a week later. “A friendly setting—one that enables you to talk, joke, and debrief with other athletes—seems to help with recovery and future performance,” says study author Christian Cook, Ph.D., professor of physiology and elite performance at Bangor University in the U.K.

The benefits of social interaction are likely rooted in evolution: “Our physiology probably evolved to reward supporting one another,” says Stanford University psychology lecturer Kelly McGonigal, Ph.D. “The basic biology of feeling connected to others has profound effects on stress physiology.” Social connection shifts the nervous system into recovery mode and releases hormones like oxytocin, progesterone, and vasopressin that have anti-inflammatory properties. “What’s even crazier,” she says, “is that oxytocin helps your heart repair. It’s pretty poetic that feeling connected to others literally fixes a broken heart.”

Following a race or hard workout, sticking around at the finish line to cheer others on or grabbing brunch with friends could help initiate a natural recovery process. “Of all the things I’ve tried to expedite recovery after intense training sessions, social interaction seems to work best,” says Steve Magness, author of The Science of Running and University of Houston track and cross-country coach. After his athletes’ hard workouts, Magness “engineers forced social interactions” in the form of team breakfasts and dinners, group cooldowns and debriefs, and game nights. Not only do Magness’s athletes report feeling more recovered after social activities, but they have seen an increase in their heart-rate variability (or the change in time intervals between heartbeats, which serves as a well-accepted indicator of recovery). Magness has found that for most of his athletes, “social recovery has a better impact on heart-rate variability than more traditional recovery techniques like ice baths and massage.”

Positive Reflections

Research from Bangor University found that athletes who receive positive feedback and focus on what they did well following a competition have a better hormonal response than those who receive and focus on negative feedback (what they didn’t do well). In particular, those who reflected upon their successes had significantly more testosterone, a hormone associated with muscle and bone repair and growth, circulating in their blood. Study authors speculate that positive reflections help athletes transition from the stress of a workout into a more restorative and confident state.

Help your body transition from the stress of a workout into a more restorative state by engaging in positive reflection. Magness makes sure to end all postworkout and postrace debriefs on a positive note. “Even if your workout or race didn’t go well, find some sort of positive and reflect on it,” Magness says. “This can be as simple as ensuring that you always finish your training-log entry with a short note about something that went well and can be built upon.” This isn’t to say that Magness and the athletes he coaches don’t discuss things they can improve, “but we make sure the balance of the conversation focuses on what went well,” he says. “We save the negative stuff for the next day, once the athletes have already relaxed and de-stressed.”