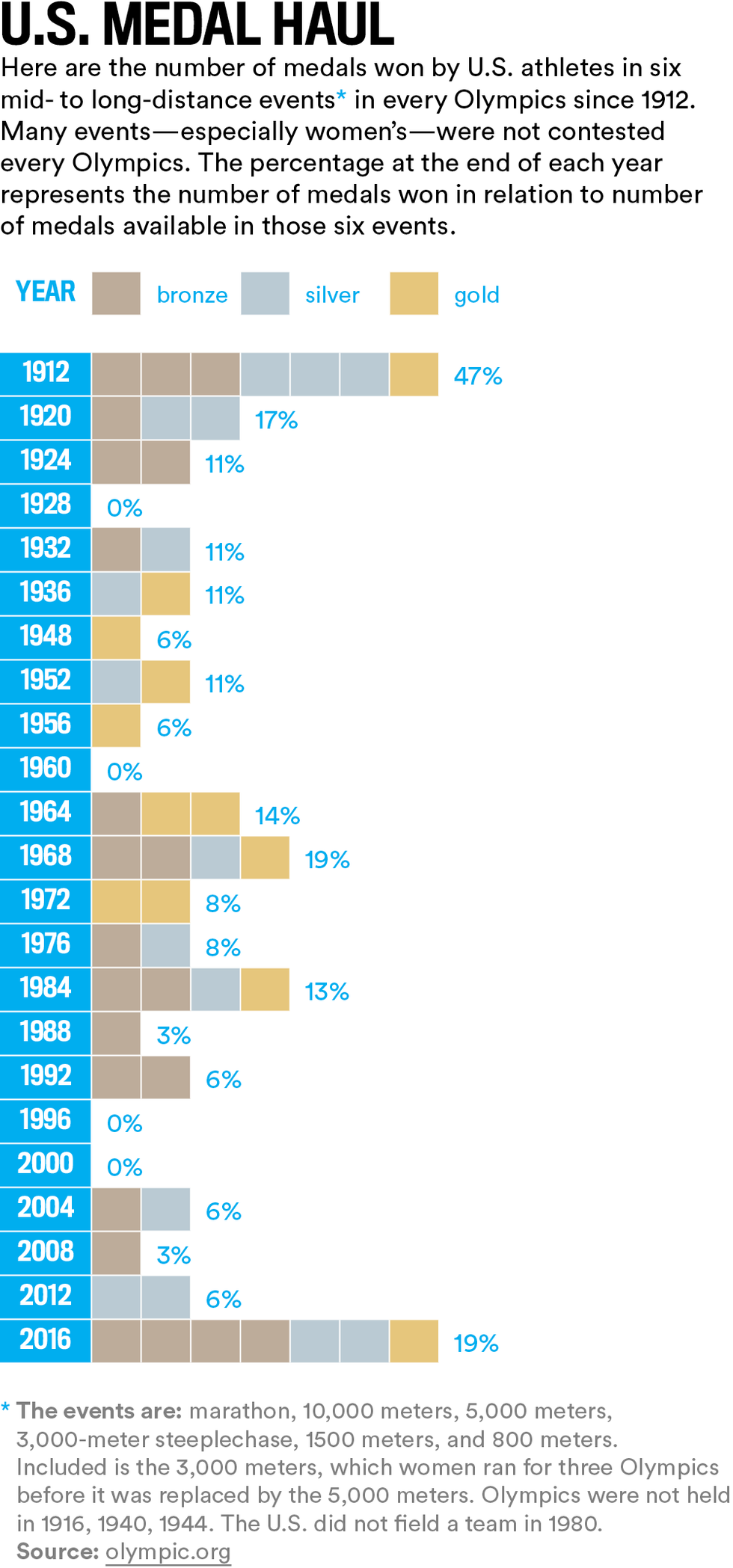

Halfway through the Olympic track and field competition in Rio, the U.S. had already earned more medals in the distance events than in the entirety of the 2012 Games in London. At the finish line of the men’s marathon, where Galen Rupp placed third on Sunday, the final tally was in: seven medals for distances of 800 meters and up, compared to just two earned four years ago.

In fact, the distance athletes earned two more medals in Rio than they did in the previous four Olympics combined and saw many others place well in the finals—all three Americans in the women’s marathon were in the top ten, for example. This year, Matthew Centrowitz (1500 meters) won gold, Evan Jager (3,000-meter steeplechase) and Paul Chelimo (5,000 meters) won silver; and Rupp, Emma Coburn (steeplechase), Clayton Murphy (800 meters), and Jenny Simpson (1500 meters) brought home bronze.

“I think it’s fantastic. It’s so exciting to see the U.S. resurgence in distance running. We’re back to where we were back in the late ’70s or early ’80s, where Americans are competing to win medals again consistently in all the events,” said Alberto Salazar, coach of the Oregon Project, which collected gold and bronze through Centrowitz and Rupp. “It’s exciting.”

The factors that conspired to produce the jump in performance are varied and largely unknowable. For example, did it help that the Russians were absent, serving a nationwide doping ban? It didn’t hurt—Russian women won three distance medals in 2012. But beyond good luck and guessing games, there was old-fashioned hard work, incredible talent, and a concerted effort on the part of U.S. officials, coaches, and athletes who bought into a high-performance initiative four years ago to help close the gap.

“After London we saw that 10 distance athletes finished in the fourth-through-eighth place positions,” said Robert Chapman, USA Track & Field associate director of sports science and medicine. “We looked at that group and asked, ‘How much do they need to improve to medal?’”

When the numbers were crunched, these runners needed an average of 0.52 percent performance improvement in order to have a better chance at landing on the podium at the 2016 Olympics, Chapman said. USATF and the United States Olympic Committee began putting resources toward that goal and invited top-tier coaches and athletes to be part of it.

Though not an exhaustive list of factors, the following are three variables that contributed to the U.S. distance success in Rio:

1. Training high

At the heart of the ongoing research was how to optimize altitude training—not a new concept, but a factor identified as having the most potential for results. Except for Clayton Murphy, all of the U.S. distance medalists live or trained at altitude, as well as 17 others who made it to the finals of their events in the 800 meters and farther. They include Molly Huddle, who does altitude stints in Flagstaff, Arizona, and set the American record in the 10,000 meters in 30:13.17, placing sixth.

The altitude emphasis harkens back to the initial concept that coaches Bob Larsen and Joe Vigil had when they started bringing top runners to Mammoth Lakes, California, after a long drought of talent. That group produced two Olympic marathon medals in 2004—silver for Meb Keflezighi and bronze for Deena Kastor.

“That dream has come true for me and to be part of [developing U.S. distance running] has been a huge reward. I hope I’ve been a small part of it,” Keflezighi said. “Now we have depth, we’re trying to be the best that we can in the world.”

Simply put, training in the thin air naturally boosts the body’s erythropoietin (EPO) production, which increases red blood cells delivering oxygen to muscles and converting it into energy. It’s a natural and legal performance-enhancer, but its effects and benefits are highly individual.

“We set up an initiative to measure the individual athletes’ responses to altitude and, from that, their coaches could design their training programs,” Chapman said. “Based on the information we could provide, coaches could make decisions like how high to train, for how long, when to go in the training cycle, what workouts to do at altitude, and when to come down to sea level to compete.”

Chapman notes that Jerry Schumacher, who coaches the seven Olympians from the Bowerman Track Club, and Mark Wetmore, who coaches Simpson and Coburn, were especially interested and invested in the initiative.

USATF provided support for altitude camps in Flagstaff and Park City, Utah, where athletes agreed to have their total hemoglobin mass measured at the beginning and end of their stints (Coburn and Simpson already live in the mountain town of Boulder, Colorado). They also measured ferritin, the protein that stores iron—normal levels are important because those with low ferritin tend to show no increase in hemoglobin mass at altitude.

“From all of this we can dial in the variables pretty close,” Chapman said. “That kind of attention to detail begins to result in those fractions of performance gains.”

2. Timing it right

Aside from the altitude research, other aspects of performance were called into question—especially after the 2015 IAAF World Championships in China last year, when Emily Infeld was the only distance athlete to medal (a bronze in the 10,000 meters).

A few reasons were revealed, including the timing of the U.S. championships, used to select the world team. It was scheduled too early on the calendar, leaving about 54 days until the world meet. Training programs can be interrupted in such a span, screwing up the periodization of stress and recovery cycles.

“I think we mistimed things last year,” Chapman said.

For the track events, about 30 days between the team selection competition and the Olympics seem to keep the runners on a preferable schedule. The U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials were held during the first two weeks of July, leaving about four weeks until the Games began. For the marathon runners, the trials were moved to February after being held in January in 2012, which allowed for a window of recovery and six months of preparation.

3. Planning for logistical challenges

One thing everybody quickly realized about holding the Olympics in Rio was that almost everything was going to be a challenge. Transportation, housing, food, water, training—nothing was going to be easy.

Chapman and others at USATF and the USOC started planning to make the trip as smooth as possible for Team USA. A nearby naval base was rented as a private training venue, which provided a track that used the same Mondo surface as the Olympic Stadium facility, weight rooms, cooks, medical staff, and pretty much anything else an Olympian might need to perform.

Suggestions for apartment and hotel accommodations in safe areas like Flamengo Park—where outdoor running was possible—were compiled, and drivers with access to Rio’s Olympics-only traffic lanes were hired, getting competitors to the track in about 25 minutes.

Instead of staying at the Athlete Village, which required at least an hour bus ride to Olympic Stadium and access to cafeteria-style food, many distance runners chose to take advantage of the resources USATF and the USOC had scouted out to keep their routines as close to normal as they could. They made sure medical staff and therapists could get in cars and to the runners who needed them between rounds of competition.

“Galen and I stayed in a house and we had a chef come every other day to cook us meals that we asked for,” Centrowitz said. “We just kind of kept things in a routine. I’ve kept things light, so there wasn’t a huge difference.”

It’s the attention to those details that put the final pieces together for many of the top runners, Chapman said.

“The logistics on the ground end up being important,” he said. “But the overriding theme for the success at this Olympics is really the collaboration between coaches, sport administrators, scientists, the USOC, and USATF. It’s a new era.”