Many top athletes race sparingly, waiting until their fitness is perfect before toeing the line. But it wasn’t always that way. In the months leading up to his American best of 2:09:55 at the 1975 Boston Marathon, for example, Bill Rodgers raced everything from two miles on the indoor track to 30K on the roads.

He enjoyed racing, but he also used minor races as stepping-stones toward two or three major goal races each year. This approach has benefits that are hard to replicate in workouts: Intermediate goals maintain motivation, and the race atmosphere pushes you to run hard. For those with prerace jitters, familiarity breeds a more relaxed approach and prepares you for adversity, says Camille Herron, a 2:37 marathoner who, inspired by Rodgers, races 15 to 20 times a year (including up to seven marathons).

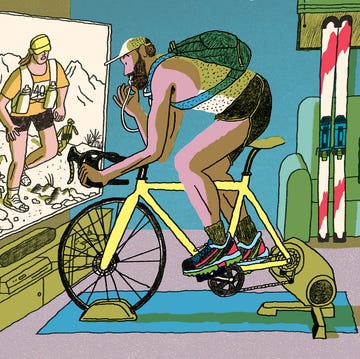

Still, you shouldn’t just sign up for a race every weekend and hope for the best. Here’s how to ensure that there’s a method behind the madness.

Race Tired

Rodgers raced 23 times in 1975, but used most as prep for the Boston and Fukuoka marathons. When he ran a three-mile indoor track race a few months before Boston, for example, it was part of a 20-mile day. You don’t have to go that far (literally), but resist the urge to be well-rested for every race. If you’re racing 10K or less, plan an extended warmup or cooldown—or both.

Apply It: At secondary races, aim to run at least three miles before and after the race. Once that’s comfortable, extend the cooldown to five miles. Give yourself at least two days to recover afterward (three days for races of 10 miles or longer) before doing another hard workout.

Diversify

Practice makes perfect, but don’t just race the same distance over and over. “The shorter, competitive races are great for learning tactics, repeated surging, and hurting in a different way,” says Herron. “The longer races are more drawn out, so you have to have greater patience and mentally and physically work through the highs and lows.”

Apply It: Find races that challenge skills you’ll need in your goal race. If you’re training for Boston, find a race with plenty of down-hills to test your quads. Challenges like early or late starts, hot or cold weather, and crowded first miles can—and should—be rehearsed at other races.

Pace Yourself

When every race is important, it’s hard to take risks. Use low-key races to experiment with pacing, and don’t worry if the results aren’t always great. You’ll develop a better feel for the differences between “a bit too slow,” “a bit too fast,” and “just right”—and you may discover that a more conservative (or aggressive) approach works for you.

Apply It: Run the first half of a race five percent slower than your current race pace, then finish as fast as you can, to learn to stay relaxed in the early miles of races. Alternately, run the first half five percent faster than race pace. It will be painful, but you’ll be practicing the hardest and most essential skill in running: hanging on.

* * *

WANT TO RUN A MARATHON?

We'll show you what to eat, what to wear, and how to train without getting injured. It's all in our new online learning course.