The benefit of the doubt began running dry for high-profile hedge fund Marto Capital in 2018. The misbehaving portfolio bucked around, losing money when it shouldn’t have, despite its architects’ monkeying with the model and goalposts. Investors wooed by Marto’s direct bloodline to Ray Dalio and Bridgewater Associates — an investment luminary and the world’s largest hedge fund — found that all-weather returns apparently skip a generation. Marto, like many young firms, had some pimples to clear up.

Yet investment chief Katina Stefanova kept pushing another subject internally: getting into cryptocurrency.

Many key staffers had already left Marto, and others withdrew in frustration. “I wanted nothing to do with any of that,” says a former employee. “There was a point in time when I just stopped asking questions.” He started looking for a new job instead.

Some of the distinguished financiers advising Stefanova cautioned against the expansion schemes, but the idea kept popping back up. Marto’s advisory committee met every few months and had no real power or legal duty, unlike a board of directors. These advisers worked for free, and many of them had personally invested money — as well as their reputations — in the fund.

Scott Kalb, a founding adviser and the former chief investment officer of South Korea’s now-$157 billion sovereign wealth fund, formally cut ties with Marto in July 2018, after precisely two years and too many crypto discussions.

“I felt that the vision was evolving in how she was investing,” Kalb explains. “It was no longer what we started out with. Then, to be honest, she wanted to move into some other business areas. I looked at that as a red flag. My feeling was that if you start a business, the first thing that you’ve got to do is establish it and make it successful before you can go off and do other things. Especially if you’re raising money, you’ve told people you’re going to concentrate your resources.”

Whether eyed out of desperation or a desire for innovation, crypto squared with Stefanova’s tech expertise and self-styled brand as a “thought leader on disruption in asset management,” as she calls herself on Marto’s website.

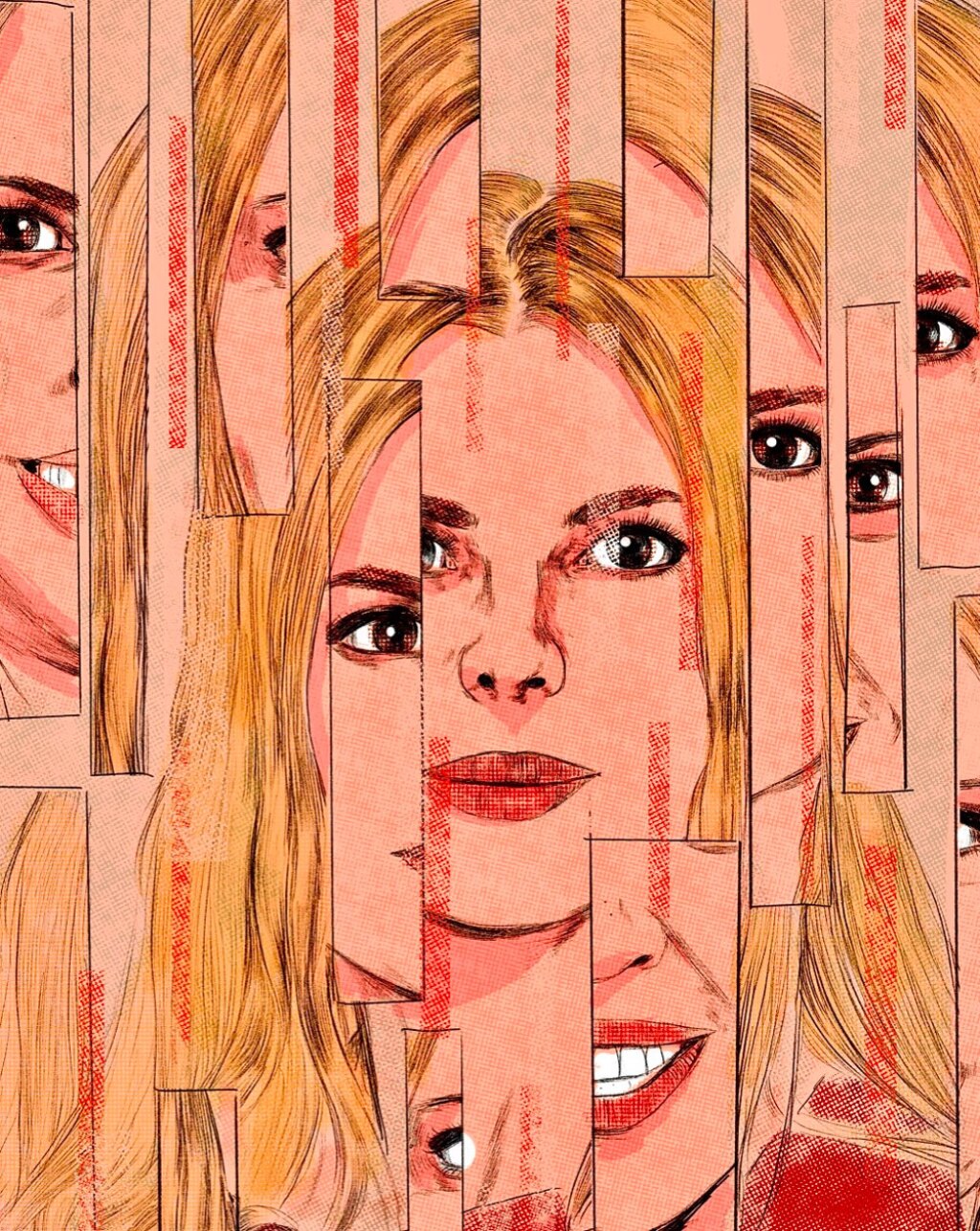

The glorious public story of Stefanova and Marto Capital has been told countless times: In Forbes, at myriad conferences, to investors in pitch meetings, and in this publication, among many others.

Here’s how it goes.

A star executive leaves Bridgewater Associates and teams up with several former colleagues to launch a new hedge fund. Marto Capital raises hundreds of millions of dollars from the most prestigious seeders of young funds, including PAAMCO Prisma. And at the helm of the hotshot spinout is a woman — a vanishing rarity in alternative investing — and one the industry desperately wants to see succeed, if only to play down its own boys-club reputation. Stefanova is rich in stamps of credibility: Bridgewater, PAAMCO, and official advisers like former GE Asset Management CEO John Myers and Charley Ellis, who served as investment chair of Yale University’s endowment, oft-considered the best institutional fund of all time.

“You had the right ingredients,” says Kalb. “Somebody who had been a senior executive at Bridgewater, which is a very successful firm, spinning out. Spinouts can be very promising. She was a woman in a very male-oriented financial world. I liked her vision and I liked her sense of technology.”

But that shiny narrative glosses over critical elements of Stefanova’s backstory and Marto’s reality.

Some are open secrets in the investment world; others have been wrapped up in nondisclosure agreements and until now only whispered about by those involved. Some people in the notoriously tight-lipped industry would not discuss the inside tale of Marto on the record. But more than a dozen former colleagues of Stefanova’s, investors Marto pitched, and others close to the situation did speak about their experiences, often insisting on anonymity. In addition to those interviews, nonpublic Marto documents, regulatory filings, copies of private correspondence, and past media coverage reveal the messier truth behind a hedge fund fairytale.

Many who knew her at Bridgewater rankle at her “rebranding” as an investment executive. “It would be like me starting a hedge fund as the chief investment officer,” explains one former client servicer. “I’m not an investor. And neither was she.” As another high-up former colleague puts it, “She was miles, miles away from any investing function.”

Stefanova counters that executive management relates as much, or more, to CIO work as stock picking or trading, and strongly denies ever misrepresenting her background. “I was never instrumental in Bridgewater’s returns,” she says from Marto’s airy and simple midtown office. (Stefanova agreed to speak on the record for this article; however, she declined to allow the interview to be recorded.) “What I was good at is bringing together a team. The founders of Millennium and Citadel never managed money.” (Izzy Englander worked as a floor trader and broker back when stock markets had floors, and later built Millennium Management into a $40 billion hedge fund business. Ken Griffin ran two hedge funds from his college dorm before founding Citadel, where he still manages money.)

Marto’s website and pitch materials give the CIO’s bio as “nine years as a senior executive and managing committee adviser reporting directly to the CEO at Bridgewater Associates and serving in critical investment and management leadership roles.” There is no mention of the back office. The “critical investment leadership” position refers to her post-MBA spell in account management, Stefanova clarifies.

According to Stefanova, Dalio identified the HBS grad’s substantial talents, and brought her into the senior team of operations and management employees. Often described as a “culture carrier,” Stefanova’s reputation “was stellar: smart, close to Eileen” — co-CEO Eileen Murray — “and Ray. But I always found it odd that she presented herself as more of an investor than she was,” says another former colleague.

Bridgewater’s unusually vague titles allow for resume-bending that is impossible for alumni of other finance giants. A “management associate,” for example, might research markets for the $160 billion portfolios or oversee food vendors. (Full disclosure: My husband is a management associate at Bridgewater, and in the past would have been one of potentially hundreds of employees in Stefanova’s reporting line.) One would never know from their title alone. The company compels honesty through strict oversight of its departed workers, nearly all of whom sign agreements barring them from competitive jobs for two years or more — in a small number of cases, their whole working lives. Plus, few alums want to get on Bridgewater’s bad side.

These ironclad noncompetes mean that if a longtime investment executive left and two years later started a hedge fund, Dalio’s machine would come down on them with full force, Bridgewater alums point out.

Marto certainly raised money off of its Bridgewater lineage. Even today, having all but abandoned its original systematic product, the relatively new sales chief, Marcus Asante, notes unprompted that “Marto’s original roots and heritage come from Bridgewater.” As alums acknowledge, Bridgewater intrigues investors. Working at the company behind All Weather and Pure Alpha is a selling point.

A 2017 email pitch from Marto’s then-head fundraiser name-checks the Connecticut behemoth in paragraph one, for example. “I would like to schedule a call or meeting with you to discuss Marto Capital,” wrote John Wasilewski to a prospective investor. The majority of the senior leadership team, he continued, “worked together at Bridgewater Associates and have a collective experience of 30-plus years working there.” Wasilewski himself among them: He spent nearly five years there, and about two-and-a-half years at Marto gathering impressive sums of money.

Marto’s investors understood that they weren’t getting All Weather 2.0 and that Stefanova wasn’t a professional investor, one insider counters. The heads of research and trading frequently did client and prospect meetings rather than CIO Stefanova, because they were the ones making investment decisions and running Marto’s portfolio. “The people who invested are well versed and smart enough that they can take Marto for a different reason than the fact that it’s a Bridgewater spinoff,” which it isn’t, the former employee says.

Three organizations sunk major capital into Marto, all of them highly sophisticated hedge fund seeders known as funds of hedge funds. PAAMCO (now PAAMCO Prisma), GCM Grosvenor, and UBS made up the majority of Marto’s hundreds of millions in assets, according to public records and knowledgeable sources.

All have since pulled their money. And at least one — PAAMCO — knew that Stefanova’s shiny Bridgewater lineage was a lot more complicated than the public story let on.

Stefanova left Bridgewater following repeated trading violations in her personal account, according to multiple people with knowledge of the situation. Stefanova counters that she was “not fired for cause, and Bridgewater can confirm this.” (Bridgewater declined to comment, citing policy.)

The firm has strict rules around how employees invest their own money: pre-approvals for trading certain securities, required holding periods, full transparency of brokerage accounts, and the like. A single transgression tends to earn a slap on the wrist, and employees in good standing make “foot faults” on occasion.

Stefanova had been caught in at least one prior violation, which had led to a warning and a $65 fine but little else. She broke the rules again, and this time she didn’t get a warning. “It was made very public, so I’m sure a litany of people who were at Bridgewater knew about it,” says one former senior Bridgewater employee. “Ray has this principle of ‘do public hangings,’ so that people know that you can get hung for doing bad shit.”

The company distributed an audio recording of co-CEO Murray confronting Stefanova about the violations, according to someone who says they listened to it. Stefanova admitted the trades were hers, per the source. Bridgewater also produced a case study and asked employees if they would fire her given the circumstances, two others say. This case study was later redacted, but still alluded to the trading breaches, according to a then-employee who read it.

Every Marto alum interviewed said they didn’t know why Stefanova left, and hadn’t asked.

Prospective investors’ calls to check her references at Bridgewater were sent to co-CEO David McCormick, but Bridgewater typically does not provide references beyond confirming dates of employment.

“Were there issues related to my personal trading? Yes,” says Stefanova when asked about the incidents, while stressing that they didn’t involve client money and weren’t insider trading or noncompliant with Securities and Exchange Commission regulations. A former PAAMCO employee involved in due diligence of Marto says the same. “I sold a position in my personal book without waiting for permission,” Stefanova says. “I rushed.” She describes her departure as on good terms, and the transgressions as a “side issue” to the bigger point of “no longer seeing eye to eye” with Dalio. How exactly they differed she can’t — or won’t — say. But according to a source close to the situation, before her dismissal Stefanova was involved in tense discussions around Bridgewater’s handling of sexual harassment claims.

This scrutiny — the fact that a journalist is asking her about the trading violations at all — shows a “hugely unequal standard” in how women and men are treated in finance, according to Stefanova. “The things that are being said about me are somewhat sexist,” she says. “There’s a lot of jealousy and scrutiny, particularly for women-run funds.”

Marto proved a glaring exception — at least for a while. Stefanova and Wasilewski, the business development head, brought money in the door from top investors. She attracted a prestigious lineup of talent, some of whom worked for free, and leased capacious midtown Manhattan offices.

Luc Faucheux joined early on, wanting a project after leaving UBS in 2016. Marto’s trading director, Ken Tremain, was an old colleague from Citi whom Faucheux had enjoyed working for. Faucheux calls himself an “adviser”; Marto lists him as “director of portfolio construction and risk” and No. 3 on its leadership team in a 2016 pitchbook.

“I kind of had nothing to do at the time, except play tennis — which unfortunately is very hard to do in a manner that brings a decent level of satisfaction,” Faucheux says. “I’d never been at the startup of a hedge fund. At the beginning, it was a very visible story. I think that a lot of people, including me, got on board for the team. It was a very pleasant, smart — at times brilliant — group of people. That makes you want to get up in the morning to get on the train from Westport to Grand Central with no immediate monetary payoff.”

Marto didn’t pay Faucheux a salary. But for a while, the prospect of a potential future payoff and experience at a promising firm were incentive enough.

As Wall Street veterans, Faucheux and Tremain filled in gaps between Marto the vision and an actual, functioning, SEC-abiding, trade-clearing, client-reporting investment operation. “In my opinion,” Faucheux says, “some of the Bridgewater people had worked in a mature and sophisticated environment where a lot was done in the background.” An investor’s job might be generating a signal from detailed research and modeling, and then “somehow the trading just happens.” But startup life requires knowing those nitty-gritty mechanics. “People like Ken and me brought an understanding of how to build a full-fledged investment operation, having experienced it at our previous jobs, which maybe were less siloed.”

He remembers these early years “with great fondness.” And he left before the wunderkind story fell apart.

According to Faucheux, he quit in 2018 when asked to step up his involvement in risk management and portfolio construction. Oddly, Marto had already been telling potential clients for more than a year that Faucheux was head of risk management and portfolio construction.

The subsequent crypto talk reached Faucheux but didn’t faze him. “When Bitcoin went to $16,000,” he remembers, “a lot of investment people were like, ‘Oh my God, we have to do Bitcoin. Can you tell me what that is?’ So it would not be surprising that you’d be at a hedge fund, see another fund being successful, and ask yourself, ‘Can we replicate that? Is that something that we need to focus on?’”

But at the time, Marto was struggling to even master its own investment strategy. Initially Marto pitched investors a “lower-volatility portfolio” with a “consistent investment process” and “attractive return stream that is uncorrelated to market betas and other investment strategies.” Instead, the fund would drop unpredictably, and in reaction staff would meddle with the model — a serious no-no for systematic funds like Marto, where investing should largely mean set it and forget it.

Institutional investors loathe unpredictability. If an Indian stock fund loses money because India’s market drops 15 percent, that’s understandable. If that same fund returns 25 percent during a market collapse, quality investors want a good answer as to why, despite their gains.

“It started to become clear to me that they weren’t doing what they said they were going to do, and the performance was out of line with the strategy,” says one professional who stepped down from Marto about two years ago. “The portfolio would be down more than it should have been, and so they would adjust the model. The thing that really troubled me was that the story started changing from an absolute-return to a relative story.” The fund would be down, and the response internally would be, “‘Well, have you seen how other macro hedge funds performed?’ It wasn’t supposed to be trading up or down with macro cyclical issues. I found that to be troubling.”

Marto’s own documents bear this out. The 2016 pitch deck compares performance to the S&P 500 and MSCI World indexes, both mainstream stock benchmarks that Marto beat but also moved out of step with — the “uncorrelated to market betas” part of its strategy. Those benchmarks were gone as of its 2017 year-end report, replaced with more flattering comparisons to the struggling hedge fund universe. The fund lost 2.2 percent that year, while the global hedge fund industry gained 3.28 percent and fellow macro/CTA funds added 2.51 percent. The S&P 500, meanwhile, returned almost 22 percent. Marto’s Sharpe ratio, a risk-return measurement, had fallen from 1.22 to 0.64 — a sign that investors were getting less reward for the risk they were taking on.

These documents come labeled “private and confidential,” and like all hedge funds, Marto isn’t required to publicly report its returns. Assets under management do appear on periodic regulatory filings, but these figures include leverage and accounts outside of the main investment fund. Five million dollars bet on U.S. Treasuries might be levered up six times, adding $30 million to the regulatory tally, but is still $5 million under any normal definition. Marto also had “subadvisory” arrangements with other funds, meaning their assets went into the reported sum but weren’t monies Marto raised or controlled.

For example, hedge fund Oxus Capital Management was technically a subadvisor to Marto, SEC filings show, but in practice ran as a standalone company. PAAMCO seeded both firms around the time PAAMCO was sold, and appears to have created a vehicle (the Cayman-domiciled PCH Manager Fund, SPC – Segregated Portfolio 210) that ties Oxus to Marto and Marto to PAAMCO in a three-tiered structure. Funds of funds often create separate vehicles for any number of knotty, SEC-driven reasons.

Oxus’s founder, Ali Hassani, never worked at Marto. He managed a separate strategy out of a different office, he confirms. Yet a story declaring “Marto Capital Hires Millennium PM to Work on Macro Portfolio” ran in trade publication HFMWeek early last year.

Starting with Stefanova at Bridgewater, and on to Faucheux and Hassani, resume disputes pop up all over the Marto story. Even the 2016 deck Marto sent to investor prospects contains a glaring error of biography. The advisory board page lists Charley Ellis as “co-chair of Yale University’s investment committee.” He had stepped down as chair in 2007, and earlier this year said he did not know he was an official adviser to Marto.

These could have been innocent mistakes and misunderstandings at a fast-moving startup, where titles didn’t matter except in looking grown-up in a slide presentation to pension funds. But as Dalio’s principles say, dots make a line.

Marto’s assets fell from about $260 million last spring to around $10 million or $20 million in its systematic fund, one former employee estimates.

Only three survivors remain on Marto’s website from the “cohesive, senior leadership team” of eight featured in 2016 documents: Stefanova, COO Adam Bochenek, and CFO/compliance chief Perry Poulos. Gone are Wasilewski, Faucheux, director of research Felix Turton, trading and quant specialist Jack Kopczynski, founding adviser Kalb, and adviser Mary Cahill, Emory University’s former investment chief. Additional advisers have joined post-launch, including Magnetar Capital founder Alec Litowitz, and remain listed on Marto’s website. A host of other roles have turned over too. An evolving company demanded changes in talent, Stefanova and Bochenek assert. Both compare Marto to quant powerhouse Renaissance Technologies, whose own internal upheavals recently came to light in Gregory Zuckerman’s book.

“There is less demand for systematic strategies right now,” Bochenek says in explaining the firm’s pivot away from its original product. Marto has struggled in good company: 540 hedge funds went out of business in the first nine months of 2019, when launches hit a nearly 20-year low, data firm Hedge Fund Research reports. But Marto has a track record of triumphing over tough environments, foremost in gathering serious money while so many others failed to lift off. Insiders decline to pin Marto’s main-fund demise solely on the market, even though that’s a convenient excuse.

“It didn’t work out,” reflects one person close to Stefanova. “She had a great story to tell. But at its very roots, the investment side wasn’t that strong of a model. In the end, there wasn’t a lot of there there.” Marto’s arc from wunderkind to washed up is at once shocking and utterly logical, given the full backstory: a non-investor starts a hedge fund that doesn’t excel at investing.

Stefanova left Bridgewater on difficult terms “and wanted to prove everybody at Bridgewater wrong,” says a former colleague. “She probably thought she could do it, given the training she received, her education, and her intellect. She can hustle.” And she will go on to hustle and succeed, those who know her feel sure.

Onetime media darling Marto went all but radio silent around 2018 — except for a largely ignored press release last January.

HGR Digital Asset Group “is pleased to announce our new partnership with Marto Capital, a leading technology-driven investment manager founded by former Bridgewater Associates senior executives.” Stefanova was quoted expressing her thrill at bringing “HGR’s crypto-native expertise into the Marto platform.” The release called Marto a “thought leader” and declared that “Marto AUM continues to grow and this year has performed in the top quartile among its peer group of global macro hedge funds.”

That partnership likely won’t continue, Stefanova now says. But there is a third act for Marto Capital.

“Most people would have gone out of business by now,” Stefanova says. “Regardless of what you write, we will still succeed.”