At 6’2” and 190 pounds, Joel Runyon does not have the typical ultramarathoner’s physique. But that didn’t stop the 30-year-old Chicago native from recently completing seven ultras on all seven continents to raise money to build seven schools in partnership with Pencils of Promise, a not-for-profit organization that constructs schools in Ghana, Laos and Guatemala. (Enjoy inspiring stories? Get .)

Other obstacles that Runyon overcame while running through jungles and the arctic: a stripped peroneal tendon, 25 mph headwinds, and temperatures so cold that his only water source froze solid.

Despite his name—and these incredible feats—Runyon insists that he isn’t a natural runner. In fact, he hadn’t run more than a 5K race until age 24.

RELATED: I Run Trail Ultras Because They’re Everything Road Races Aren’t

His story begins in 2009, when he graduated college in the midst of the financial crisis. Runyon spent the first nine months post-graduation unemployed and living in his parents’ basement.

“I had all of these things I wanted to do, but they seemed impossible,” he recalls. In an effort to motivate himself, he made a list of these challenges and decided to attempt one of them: finish a triathlon.

Knowing little about the sport or the training process, he signed up for a race with his local gym. The entire event lasted an hour—it included a 10-minute swim in a pool, a 30-minute bike ride on a cycling machine and 20-minute run on the treadmill. Feeling inspired, he signed up for more triathlons. Eventually, he worked his way up to a Half Ironman, which, he says, is how he tricked himself into becoming a runner.

“There is a lot of gear involved with triathlons,” explains Runyon. “But with running, there is no excuse not to run—you just get a pair of shoes and go out and do it. It’s a cheap drug you can take with you anywhere.”

And so Runyon kept running, seeking out bigger, more daunting challenges. He also began blogging about his quest to do the impossible and even founded a company, IMPOSSIBLE, inspiring others to do the same.

Soon, he was running marathons. Then, Pencils of Promise reached out. Would he like to run an ultramarathon to raise funds to build a school? He would, and he did. In 2012, he ran 50K in Chicago and raised a little over $26,000, enough to build a new school in Guatemala.

That next year, he visited the school in Guatemala, met the children he’d helped and realized he wanted to do more.

“For a lot of kids on a global scale, getting an education is truly impossible,” says Runyon, citing lack of access and funds. “Basic level education is a huge driver in elevating people to have more possibilities.”

That “more” came in the form of The 777 Project, an initiative he launched in 2014. The goal: run seven ultramarathons across all seven continents and raise $175,000—enough to build seven new schools with Pencils of Promise.

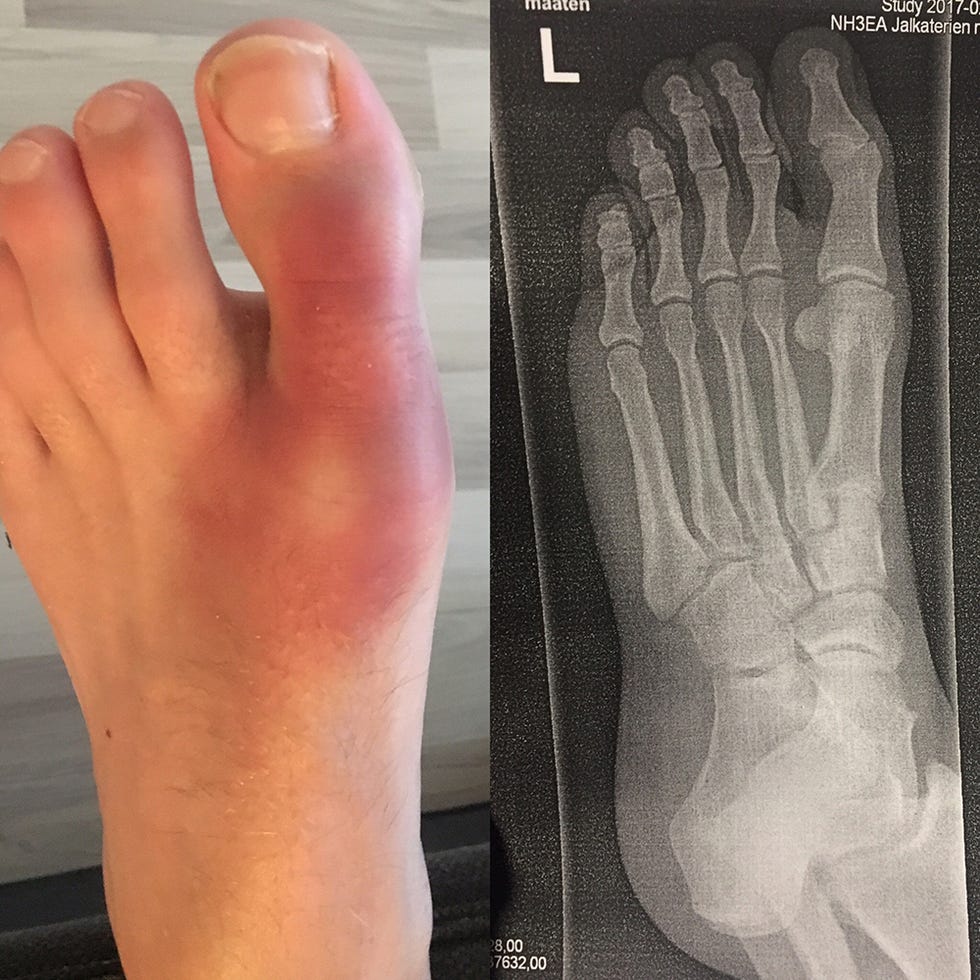

His first race: a 63 kilometer (39.14 mile) trek along trails and packed gravel roads at the Patagonian International Marathon in September 2014. All was smooth sailing—until mile 26, when 25 mph winds blew Runyon sideways across the road. He rolled his ankle and stripped his peroneal tendon. Thinking it was just a bad roll, he hobbled on for the remaining 13 miles. That decision proved dangerous, and Runyon had to do rehab for the next six months just to gain back his mobility. Then, another obstacle: The 777 Project got entangled in a trademark lawsuit, bringing the entire endeavor to a halt.

RELATED: Ask the Doctor: Peroneal Tendon Pain Persists After Marathon

“I was really scared to launch 777 at first, and then I got hurt right away and hit with the lawsuit,” says Runyon. “I was tempted to just give up and could have rationalized it.”

But he reminded himself that setbacks are okay—in fact, they’re part of the journey—and that hard work and patience pay off in the long run.

So 18 months later, after settling the lawsuit and silencing the inner voice that told him it was okay to quit, that he’d given the project best shot, Runyon quietly picked things back up again by completing 50 kilometers at the Chicago Lakefront 50/50 Ultra in October 2016.

“I didn’t really announce that I was doing it,” Runyon explains. “I just wanted to fix my head and remind myself that I could keep going.” The tactic worked, and with renewed confidence, Runyon signed up for three more ultras, all within the first six weeks of 2017.

RELATED: Moving Forward, Despite the Setbacks

First on the docket: the Narrabeen All-Nighter Marathon in Narrabeen, Australia, which Runyon thinks back on as the most mentally challenging of all seven races. In the overnight event, which takes place on New Year’s Eve, participants run a 5K out-and-back course as many times as possible within 12 hours. Runyon ran 42.5 miles.

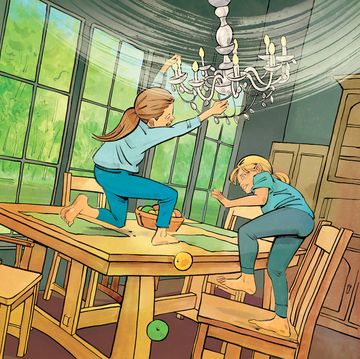

“For the first three or four hours, there were tons of people out of the course and it was still light out, so that was exciting,” recalls Runyon. But then the sun set. And as 2017 crept closer, Runyon found himself running solo through a pitch black forest, his bobbing headlamp the only light as the sounds of chirping creatures surrounded him. Eventually, even the crickets went to bed, and Runyon soldiered on, running back and forth between the endpoints.

“The out-and-back course was mind numbing,” remembers Runyon. “After you run by the same tree 18 times, you don’t want to see it one more time.”

But giving up simply wasn’t an option for Runyon. “Sometimes I’d have to turn my watch face around and just look at my feet and not do anything else but count to keep them going,” he says of these particularly challenging moments. A mantra that he often repeated to himself: Not dead, can’t quit.

RELATED: Mental Tricks to Push Through Midrace Pain

“It flows pretty well when you’re running, and you can just say it to yourself over and over again,” he says. “I often talk to myself during races. I’ll look like a crazy person muttering to myself on the side of a mountain.” (There’s some scientific research that shows talking to yourself during a race can be effective.)

Another mental tactic: negotiating with the race. “I’ll say to myself, The only way I’m not finishing this race is if I break or leg, or if a tornado comes through and destroys the trail. I’ll decide at the beginning of that race that I’m not going to let anything stop me.”

Runyon is the first to admit that this never-quit mentality can land him in trouble. He cites the fact that he ran 13 miles on a strained peroneal tendon during the Patagonian race as one example.

“From a medical standpoint, some of what I do is probably not recommended,” says Runyon, “But I write a lot on my website about not taking excuses. I’m pretty ruthless with excuses.”

That ruthlessness helped him two weeks later when he competed in the Antarctic Ice Marathon, which he describes as “the most ridiculous” of the seven races. “I was pinching myself the entire time,” he remembers. Mere hours after landing on a glacial runway, he embarked on the 100K (62 mile) trek with nine other runners. During certain portions of the race—which consisted of ten 10 kilometer laps—Runyon saw no other humans or wildlife.

“It was white everywhere, and you couldn’t judge distances,” he recalls. He wore special sunglasses to protect his eyes from snow blindness. Because it was summer there, the sun never set, making the hours, and the laps, bleed together. Nearly 18 hours later, he finished and began turning his thoughts towards the next race, scheduled just two weeks later in diametrically opposite conditions.

That next race—The North Face Thailand 50K—was “the race that tried to break me,” says Runyon. The race took off on a single track for two brutal uphill miles. The downhill portion was no easier, as Runyon struggled to keep his footing on top of slippery rocks and mud while also swatting trees and branches out of the way. “It slowed me down so much and zapped so much energy,” Runyon explains. “I was super hot and sweating like none other. My legs were completely zapped and we had another six to nine miles to go.”

He wrestled with the temptation to skip portions of the race and thus disqualify himself, but pushed through by picturing the schools he was helping to build, and reminding himself of the hurdles he’d overcome in previous races.

“I reminded myself that I didn’t run this race to be really comfortable or have it all be easy,” says Runyon.

He finished in about eight and a half hours and today describes the experience as the hardest 50K he’s ever done. “I was so confident for the first 18 miles, but then just kind of fell off the map,” he laughs. “It was a good humbling experience and a reminder to not get too cocky in the middle of the race.”

He had little time to dwell on the rough experience. Next up: the Rovaniemi 66K (41 mile) Arctic Ultra, a self-supported race in Finland. The course contained five checkpoints, only one of which had water. This was especially unfortunate for Runyon, whose water bladder broke 10 minutes before the race began. He grabbed a water bottle instead and drank it dry just nine miles into the race. He then resorted to Plan C: eating snow. In the negative 15 degree conditions, Runyon got lost three times along the route, mistakes that caused him to run an extra two and a half miles.

“There were points there where I was hurting,” says Runyon, “but I decided that I didn’t care how long it was going to take me, I was not not going to finish.” The suffering dissipated when the Northern Lights showed up the last mile of the race.

RELATED: Why Winter Marathon Training is Better

Runyon finished his last ultra—the 34.8 mile Two Oceans Marathon in Cape Town, South Africa—in April. To date, he’s raised more than $155,000 for Pencils of Promise. He’s now waiting to hear back from the Guinness World Record folks to confirm that he is the youngest person to run 7 ultras on 7 continents.

So what’s next on his impossible list? “After Cape Town, I said ‘I’m done—I’m not running for a long time,’ ” laughs Runyon. Of course just a few weeks later, when traveling through Europe, he decided to cross the countries Liechtenstein and Monaco. “As soon as I hear of something cool, I feel compelled jump on it,” Runyon laughs.

All this running is a bit surprising for someone who claims to “not always love running for running’s sake.” What Runyon does love about the sport: getting to the place where you want to give up and you’re tired, but you decide to keep going and pushing through.

“Just because it’s hard or you have a setback, doesn’t mean it’s over,” says Runyon. “It’s only over when you walk off the course.”

Above, watch these other stories of runners who have changed people’s lives.

Jenny is a Boulder, Colorado-based health and fitness journalist. She’s been freelancing for Runner’s World since 2015 and especially loves to write human interest profiles, in-depth service pieces and stories that explore the intersection of exercise and mental health. Her work has also been published by SELF, Men’s Journal, and Condé Nast Traveler, among other outlets. When she’s not running or writing, Jenny enjoys coaching youth swimming, rereading Harry Potter, and buying too many houseplants.