For Nike’s Breaking2 team, the clock is ticking. The height of the spring racing season, when their assault on the two-hour marathon barrier is slated to occur, is just a few months away, and whatever progress they and their runners—Eliud Kipchoge, Lelisa Desisa, and Zersenay Tadese—hope to make toward that barrier needs to be well underway.

To that end, a team of Nike scientists and designers just returned from a two-week trip to Kenya, Ethiopia, and Spain, where they met with each of the runners and their coaches and support teams in their home training environments. (Tadese is from Eritrea, but was training with his coach in Spain.)

During each leg of the trip, I had a chance to check in by phone with Brett Kirby, the lead physiologist at the Nike Sports Research Lab; Andy Jones, a researcher at the University of Exeter who is perhaps best known for his work with women’s marathon world-record holder Paula Radcliffe (well, that plus beet juice); and Philip Skiba, a sports medicine doctor, physiologist, and coach based in Chicago. (For details on the rest of Nike’s scientific team, see this Nike release.) Here are a few highlights of what I learned.

Kenya

The training environment in the Kenyan Highlands is justifiably famous, with hundreds or perhaps thousands of aspiring runners pounding the rutted dirt roads in pursuit of glory. Still, it was an eye-opening experience for some of the scientists to see the simplicity of the camp where Kipchoge trains, a half-hour drive from the city of Eldoret. “It’s very humbling to see the Olympic champion hauling up cold water in a bucket from a well after his workout,” Skiba said.

Kipchoge is the undisputed star of the group, and from a training perspective the team was mostly happy to observe the work that Kipchoge’s coach, Patrick Sang, prescribed. While they were there, he did a track workout of 12 x 1200 meters with 2:00 rest, hitting about 69 seconds per lap—at an altitude of over 7,000 feet, meaning there’s only about three-quarters the amount of oxygen that would be present at sea level. For those keeping track at home, two-hour marathon pace is 68.3 seconds per 400-meter lap.

During the workout, Kipchoge was fitted with various pieces of gear and apparel, such as AeroSwift tape on his inner calves. His muscle glycogen stores were assessed before and after the workout, and he wore a device that measured his muscle oxygenation in real time during the workout.

The pattern of muscle oxygenation gives some hints about whether the effort level is sustainable, Jones explained. If it drops to a steady plateau during each rep, that suggests you can maintain the pace for a long time; if it keeps dropping throughout each rep, you’ve got a problem. Kipchoge’s data during the workout—which the athlete examined with great interest afterward—suggested he was in a state of “stable physiology,” capable of maintaining that pace.

A few days later, Kipchoge did a 40-kilometer long run—a progressively accelerating effort that started (as many runs in Kenya do) with a massive pack of dozens of runners, and finished with just four at the front. The Nike team followed in a van, zooming up to give Kipchoge a carbohydrate drink every 10 minutes or so. If that seems like a lot, that’s because it is: In standard by-the-books marathons, runners get aid stations only every five kilometers, so drinking that frequently will be an adjustment.

And what did Kipchoge think of all this? When I spoke to him by phone, he was his usual calm and confident self. Through December and January, he was mostly focused on mileage and “gym work,” building overall fitness; the track workout the Nike team witnessed was his first one of the year. Going forward, he and Sang don’t plan to radically alter the training that has worked for them in the past in an attempt to get to two hours. The workouts will be similar, he said, “but my mind will be different.”

Ethiopia

In contrast to the rural serenity of Kenya, Lelisa Desisa’s training environment, just outside the sprawling metropolis of Addis Ababa, was “controlled chaos.” Desisa is holed up at Yaya Village, the training center set up by running legend Haile Gebrselassie, with hot running water and electricity. The fundamental work of training, however, is the same.

Desisa also did a track workout of 1200-meter repeats, with 1:00 rest, but his repeats got progressively faster—an approach designed to allow the scientists to test his lactate profile. At 8,800 feet above sea level, he reached two-hour marathon pace, or 68 to 69 seconds per lap, before stopping. A few days later, he did a long run of 35 kilometers at 5:20 per mile pace, again trying to drink every 10 minutes.

This was one of the big contrasts between the runners. While Kipchoge is already well-versed in trying to get enough carbohydrate in during marathons, Desisa and his training partners are accustomed to drinking little or nothing. During the long run, the team tried to offer Desisa a total of about 1.5 liters of fluid. During a debriefing the next day, Desisa reported feeling that he had drunk “a lot” during the run—but in fact, he had consumed just 400 milliliters, or less than one third of the goal amount.

Given that Nike’s sub-two attempt will be held in “optimal” (i.e., cool) environmental conditions, dehydration is unlikely to be a serious problem. But glycogen depletion will be a problem, so figuring out a way to get carbohydrates in will be a major challenge. The team is aiming to provide 60 to 90 grams of carbohydrate per hour; Kipchoge is accustomed to 30 to 40 grams per hour, while Desisa and Tadese are accustomed to almost nothing.

Using more concentrated drinks makes them harder to stomach, but using diluted drinks requires downing a high volume of fluid. This is a logistical puzzle that the Nike team is still working on, and that the athletes are practicing.

For Desisa, seeing the drop in glycogen stores from before to after his runs, and looking back at some of his recent marathon struggles, such as dropping out in New York City last November, was instructive. “I think the penny dropped,” Jones said.

Another insight about Desisa: He’s a mileage monster, racking up more than 200 miles a week, but with basically no running (so far this year) at faster than marathon pace. While there is time over the coming weeks to incorporate those speedier workouts, this is something the Nike team hopes to see more of, to make sure he can handle the 4:35 miles required for a two-hour race.

Finally, the team had Desisa practice running in aerodynamic formation with his training partners—something that comes less easily to him than to Kipchoge and Tadese, who both have years of experience running in tight formation in track races.

Desisa was seen by some observers as a surprising choice for the project, given his somewhat checkered recent marathon history. I asked the team more about what they’d seen in Desisa, and they said that his lab numbers—VO2 max, lactate profile, running economy—were particularly good. In fact, no matter what criteria they used to rank their various contenders, Desisa was always in the top three—something that not even Kipchoge could match.

But there was also an intangible element. Watching him run in the initial tests, Kirby recalled, “he portrayed confidence and strength.” He seemed like someone willing to undergo challenges, and who would respond well to those challenges.

And given what they’ve now seen about potential areas for improvement, like in-race nutrition and drafting, they’re not second-guessing themselves. “After the visit to Ethiopia, I feel even better about our choice of Desisa,” Kirby said.

Spain

When I chatted to Kirby after his first day in Spain, he had just one thing to say about Tadese: “This guy is a stud.” Given that he’d just come from watching Kipchoge, the reigning Olympic champion, train, that’s high praise indeed.

Tadese followed a similar program to the other two, with a progressive workout of 1200-meter reps and a long run a few days later. Because he was at sea level (he’s now back at altitude in Eritrea), his times were quicker: his final 1200-meter repeat was run at 62 to 63 seconds per lap.

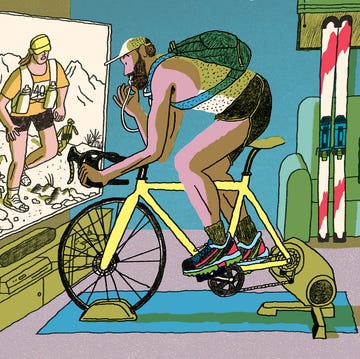

His 35K long run, which he ran at close to 5:00 per mile pace, was in a park, so the Nike scientists were forced to ride bikes instead of following in a van—a not insignificant challenge. “I was struggling to haul around this cruiser bike that we rented in Madrid, around this park, on these small rolling hills into the winds, and Zersenay is just trucking through it,” Kirby said with a laugh. “A couple times, I had to just really gut it down. I thought, ‘I’m not going to make two hours!’”

Unlike the other two runners, Tadese doesn’t train with a big group, so practicing the drafting formation will be harder. That said, Kirby pointed out, Tadese started his career as a cyclist, so he understands the importance of aerodynamics, and realizes that he will need to practice running in tight quarters.

One possible red flag in Tadese’s lactate testing: the large gap between his “lactate threshold” and his “lactate turnpoint.” As you run at progressively faster paces, you’ll eventually reach a point where lactate accumulates in your blood more quickly than you can remove it. The rate at which it accumulates is linked to your ability to sustain that pace for long durations (e.g., two hours).

The first point where lactate starts to creep above baseline levels is called the lactate threshold. At a somewhat faster pace, lactate will start to climb much more rapidly; this is called the lactate turnpoint. Marathon pace tends to be somewhere between these two goalposts; for very good runners, it should be just below their lactate turnpoint.

Tadese’s testing shows that he has a very high turnpoint—that is, he can run extremely fast before lactate really shoots up. However, his lactate threshold is unexpectedly low, meaning that small amounts of lactate begin to accumulate earlier than you would hope. This is a pattern that’s more typical of middle-distance runners than marathon runners, and will drag his marathon pace down a bit.

The advice the Nike team gave his coach: Focus on accumulating more volume in the training zone between lactate threshold and lactate turnpoint, with tempo runs, fast steady runs, and long intervals lasting between three and ten minutes. While the other two runners have a big endurance base but still need to add speed, Tadese has all the speed he needs but should work on sustainability.

The overall take, and the next step

Predictions are perhaps a fool’s game. (Don’t believe me? After I pointed out that Ladbrokes was offering bettors the chance to double their money by betting against the Breaking2 project, the betting line was promptly removed.)

Still, I pressed the team for their revised take on whether they were on track for a sub-two. It’s worth pointing out, again, that Andy Jones was closely involved with Paula Radcliffe’s world-record marathons. While I’ve been very enthusiastic about recent research showing how the brain influences endurance performance, Jones has always been a sobering counterweight to these enthusiasms. With sufficient physiological data, he believes, you can get a pretty good idea of what an athlete is capable of.

In fact, he told me, when Radcliffe was preparing for her marathon debut in 2002, he told her that her lab data suggested she was capable of running 2:18—a bold claim given that the world record at the time was 2:18:47. She went on to run 2:18:55 in London.

Later that year, he told her she was ready to run 2:17. She ran 2:17:18 in Chicago.

Finally, in 2003, he told her she was ready to run 2:16. She ran 2:15:25 in London, which remains the world record.

So, given that history of prognostication, I asked him what the numbers foretold for Kipchoge, Desisa, and Tadese.

Kipchoge, he said, was difficult to predict, because his visit to the lab for testing had been his first time on a treadmill. When I visited Nike HQ in Oregon last year, I saw Kipchoge’s second treadmill testing session, and I can attest that he looked extremely uncomfortable—like Bambi on ice. So his lab numbers probably don’t reflect his actual potential; but his London Marathon win last year tells us that he’s at least capable of 2:03:05.

“The other two,” Jones told me, “do look like they’re capable of 2:02, 2:03, 2:04, something like that, on the best possible day, which is kind of the area that we’d need to be if you add in all of these other factors like the drafting and the footwear and other bits and pieces that might get you closer to two hours.”

RELATED: FAQ About the Sub-Two Quest

In a sense, then, I’d argue that much of what Nike is doing with things like nutrition, monitoring training, and optimizing weather is not so much an effort to make the runners faster, but rather to reduce the odds of a screw-up. Compare the credentials of the runners at any major marathon with the actual results, and you see that running up to your potential on any given day is a very low-odds proposition. So Nike wants to make sure that its runners are ready on the day to produce a 2:03-ish effort—and then the details like the course and the “other bits and pieces” will hopefully do the rest of the job.

What will those bits and pieces look like? We’ll get a look very soon, because the runners are scheduled to try a full dress-rehearsal over the half marathon distance.

It’s still hard to place a solid bet at this point—but I’ll give the last word to Kipchoge. I asked him if people in Kenya thought his goal was feasible. “Most of the people were saying they will die before they see a man running under two hours,” he replied. “But I think I will prove them wrong.”

***

Discuss this post on the Sweat Science Facebook page or on Twitter, get the latest posts via email digest, and check out the Sweat Science book!