Editor’s note: This story originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of Runner’s World. At the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, U.S. steeplechasers Evan Jager and Emma Coburn won silver and bronze, respectively. For the latest on the 2021 U.S. Olympic team, check out our extensive Olympic Track and Field coverage.

Long before the Kenyans owned the steeplechase, it belonged to the crazies.

Men (alas, it was always men, until recently) who craved a brutish challenge and had little regard for their own well-being, the story goes, would race from one town’s church steeple to the next, hurdling all manner of wet and dry obstacles along the way. Those early steeplechases, in Ireland, tended to involve horses, at least to start. In one of the earliest documented human steeplechases, held in 1838 in Birmingham, England, the competitors had the good sense to spare their families the shame of association, and adopted pseudonyms: The Spouter edged Neversweat over a mile-long course, with Sprightly, Rustic, and Chit-Chat trailing behind.

A dozen years later, at Oxford’s Exeter College, a chagrined jockey named Halifax Wyatt, fresh from being tossed off his mount in an equestrian steeplechase, invited his peers to race on foot. They established parameters that roughly resembled the modern event—two miles, with 24 jumps—but staggered across a course of marshy farmland that decidedly did not. Sport historian Montague Shearman later wrote: “…the ground was deep, the fences big, and all the competitors were heavily handicapped by wet flannels bedraggling their legs.” Wyatt won the slog, though about half of his 24 competitors dropped out after a few hundred yards.

As cinder-track racing emerged in the late 19th century, the steeplechase fell out of favor except as a sideshow. Meet organizers designed impossibly long water jumps, Shearman wrote, “to please spectators…for the British public, in the true style of those who rejoice in gladiatorial shows, like to see somebody…coming to grief or rendered ridiculous.”

The steeplechase made its Olympic debut in Paris in 1900, with one 2500-meter race and a 4,000-meter gauntlet; Sidney Robinson of England, a real masochist, medaled in both. It wasn’t until the 1920 Games that organizers settled on the single 3,000-meter race that is still run today.

Over time, other standards were established: There are a total of 35 jumps in a steeplechase, each 36 inches high for men and 30 inches high for women—roughly the height of a Great Dane. Most of the jumps are meant to be leapt over, but seven require jumping onto a fixed hurdle then pushing off of it over a 12-foot-long water pit, which begins at a depth of a little over two feet and slopes upward. The total number of laps can vary slightly depending on the placement of the water jumps, but in the Olympics today it’s seven-and-a-half.

With all those impediments, the Olympic steeplechase has always been a haven for carnage. The great “Flying Finn” Paavo Nurmi claimed silver in the 1928 contest only after recovering from a back-first splash into the pit during his heat, in an incident that has been described as “almost fatal.” Dry hurdle crashes cost East German Frank Baumgartl possible gold in 1976 (he’d settle for bronze) and Kenyan Brimin Kipruto a shot at his second steeplechase gold in 2012. Matthew Birir, of Kenya, fell after being spiked on the third lap in 1992, but managed to rally to victory despite a ripped shoe. The last time an American won gold was in 1952, when Horace Ashenfelter, an FBI agent who trained by hurdling a park bench in New Jersey, defeated Vladimir Kazantsev after the Soviet favorite stumbled out of the last water pit. (The same fate befell Tanzanian Filbert Bayi in 1980.) And where the barriers fail to destroy, crippling fatigue takes over: In his bid to reassert American supremacy in 1984, top-ranked Henry Marsh fell behind early and surged late to be the fourth man across the line, where he collapsed and was carried away on a gurney.

To even whiff glory in the steeple is to become familiar with unique, intimate agony. It’s a gorilla that jumps on your back in the last lap, after you’ve survived the first 24 hurdles and six water jumps, dragging you down into the track so that the maw of the final pit can consume you. You must become the beast in order to defeat it; Kip Keino won gold in 1972 by hurdling, he said, “like an animal.”

The event’s dirtiest trick is that it feels fine until, suddenly, it doesn’t. A PR pace in the 3K steeple roughly equates to that of a 10K—if you start any faster, you’re doomed. Evan Jager and Emma Coburn, America’s best steeplechasers and legitimate gold-medal threats in Rio, know this all too well. “When you go out at PR pace, you feel good because you aren’t running that fast, and then it’s like a slow death,” says Jager. “You’re just trying to keep your s--- together.”

Says Coburn, wincing: “The pain creeps up on you in such a nasty way.”

Jager, 27, and Coburn, 25, are already all-time national greats. The seven fastest races ever run by an American man all belong to Jager, and eight of the top 10 for women are Coburn’s. Combined, they are the rising tide lifting our domestic steeple stock: The United States has never been deeper in the event, and at Worlds in Beijing last August all six men and women advanced to the final for the first time ever in a global championship.

The U.S. has not had an Olympic medalist in women’s steeple since it debuted in 2008, and Brian Diemer, who edged Marsh for bronze in 1984, was the last to win one on the men’s side. Jager and Coburn have a chance to end both droughts. If you believe in things like destiny, it would seem fortuitous that they first met at the Olympics four years ago. Each has been among the other’s biggest fans ever since.

Neither faces an easy path. Kenya has dominated the men’s event, winning gold (and most of the silvers and bronzes) at every Olympics they’ve participated in since 1968. The women’s global championships have been scandalized by doping. Before Coburn and Jager can even consider their international prospects, though, they must first survive the U.S. Olympic Trials this month in Eugene, Oregon. The requisite top-three finish for each should be a virtual guarantee, but this is the steeplechase. Failing to clear a hurdle by even a fraction of an inch can be the difference between history and, well, something else entirely.

Ronaldo Field, still damp from the previous night’s rain, sparkles in the morning light. Geese honk in the distance on this Saturday in early March. Around the pitch, situated in the middle of Nike’s sprawling Beaverton campus in Oregon, six runners jog in a loose V-formation, shedding layers as the sun warms them. Jager leads the way, loping along with leggy, effortless strides. A sports watch turned in on his left wrist keeps the group on a roughly six-minute-per-mile pace for the 75-minute workout; on his right wrist, always, is a hair tie.

His lustrous mane bobs lightly beneath a backward Nike SB cap, and his Bowerman Track Club teammates fan out in its wake, like the high school girls do when they’re in town for Nike Cross Nationals. He is a heartthrob, no doubt, but all comers should know that he got engaged over the Christmas holiday to his longtime Swedish belle, Sofia Hellberg-Jonsen. Getting her to agree to marry him, on a snow-globe Stockholm night, is his proudest accomplishment. Not crushing the American steeplechase record months after taking up the event, or running in the Olympics weeks after that, or even flirting with the vaunted eight-minute barrier in Paris last July. That’s where the track world fell in love with Jager, in Paris, though his memories of it are far from romantic.

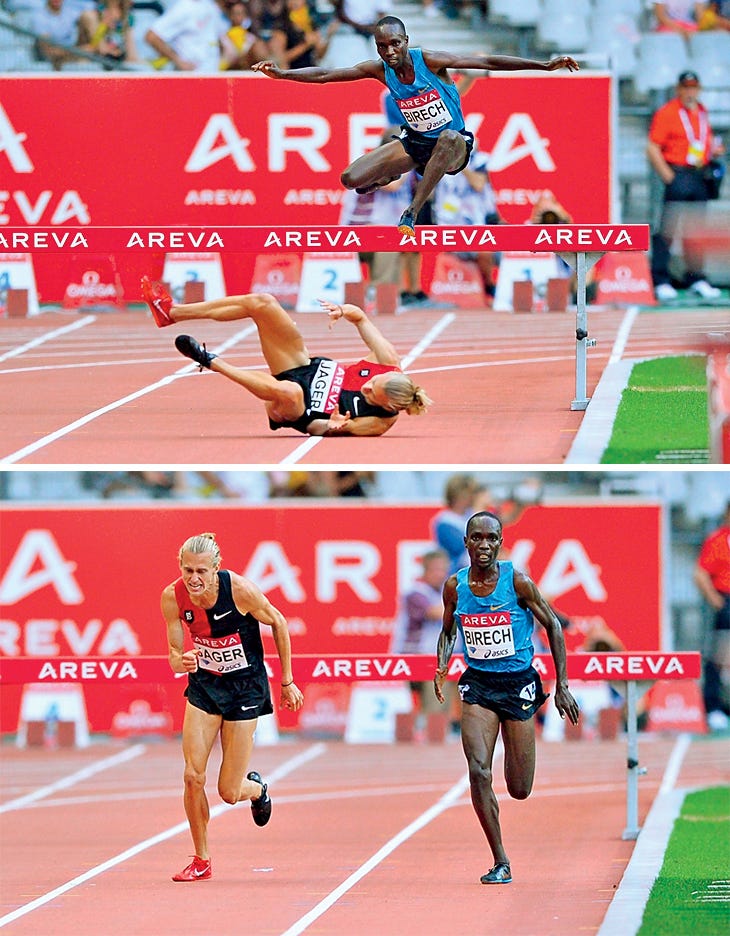

It is the last lap of the Paris Diamond League and Jager is toasting one of his primary Kenyan rivals, Jairus Birech. Jager is in the best shape of his life. Three weeks earlier, in what should have been a tuneup 1500-meter race in Portland, he scorched all expectations by running a 3:32.97, the fastest time ever for an American-born athlete on U.S. soil. Now in Paris he is laying waste to the notion that Americans can’t hang with Kenyans at full throttle. It is Jager who has had his foot on the gas for five laps before passing Birech, who is fading, fading. Jager looks at the clock for the first time heading into the bell lap. S---, I might be able to break eight minutes, he realizes. It’s one of running’s magic numbers, albeit a little under the radar. Only 11 men have done it, whereas 29 have gone sub-2:05 in the marathon.

With 300 meters to go, Jager sees on the big screen that his foe remains a good five-plus meters behind him. Jager clears the last water jump, lands cleanly—and feels all of his energy drain into the pit, down into the void. Still, he retains a healthy lead. Fumes can still get him there. Focus, just make sure you get over this last barrier…

The trigger is almost imperceptible. Replay the clip on YouTube a few times over and you notice his trail foot barely clips the last barrier, by a toenail. That’s all it takes. Right foot clean, left foot askew. Down in a heap. There goes Birech, already a sub-eight man, on his way to the fastest steeplechase anyone will run in 2015.

And then an incredible thing happens: Jager scrambles to his feet, sprints his ass off, and leans valiantly into an 8:00.45 finish, an American Record. A time bettered only by Birech’s for the year, and an effort that would earn Jager universal admiration from the track world. The Diamond League declared it the “Moment of 2015.”

“I probably gained more attention for falling and running that time than if I’d run cleanly and gotten 7:57,” he’ll tell me later, a tad sheepishly, while curled up like a cat in an oversize beanbag chair in his Portland apartment.

In the ‘80s there was Marsh, who set the U.S. steeplechase record four times, was number one in the world three times, and competed at two Olympics. In the ‘90s there was Mark Croghan, who made three Olympic teams and was the second-fastest American ever, until Daniel Lincoln came along in the aughts. Lincoln broke Marsh’s 21-year-old record in 2006 and went to one Olympics. Jager broke Lincoln’s record in 2012 mere months after picking up the event, but not until Paris did it become clear that he not only could but should accomplish something none of that talented trio had: win a global medal.

Coburn sits at the wheel of her dirt-flecked Audi SUV, texting her training partners about a backup plan. It’s late February, and the Anvil of God trail, where they’d planned to run, had been shut down by snow. Poking into the front of the vehicle from its gutted backseat is a shovel that she uses on speed days to clear off the University of Colorado’s practice track. Boulder’s capricious weather won’t get in the way today, either: We’re off to the flatter, drier Bobolink Trail, which links up with the school’s cross-country course.

Coburn graduated from Colorado in 2013 and never left. This is home. Her parents met at the school, and she and two of her three siblings were born in Boulder. The Coburns moved away to the tiny mountain hamlet of Crested Butte, 8,885 feet up, when Emma was 7, but she eventually came back down to Boulder to run for Mark Wetmore’s and Heather Burroughs’s powerhouse program. She signed her first pro contract with New Balance but stayed with her coaches, and now lives in a new mixed-use complex developed by her father, built on land that was once a steel fabrication yard owned by her grandfather. Yes, her roots run deep here.

Coburn pulls off onto a Highway 93 service road where Sara Sutherland, who runs for Saucony, and Blake Theroux and Aric Van Halen, ex-Colorado runners who train with Wetmore’s group, all stretch out under a dazzling blue sky. Snow clings to the Flatirons in the distance and to the shadows down here, but the temp will push 70 today. Coburn, wearing a black tank top, red racing shorts, and black New Balance Zantes, pulls her hair into a ponytail and jogs to a dirt path just off the road.

Even for an easy day, Coburn’s gait seems unusually effortless. From her hips up you’d barely know she’s running, if not for her swaying hair. It’s something that she’s known for: an uber-efficient, rotary stride that hardly perturbs her upper body, even in a steeplechase. A week later in Portland, Jager will jealously imitate it with two gangly fingers, deftly curling one back to demonstrate her low-key hurdling form. Coburn’s New Balance teammate and frequent training partner Jenny Simpson says it takes some getting used to. “It always looks easy,” she says. “She’ll be out on American Record pace and you’re like, ‘Why aren’t you trying any harder!?’"

It’s how Coburn looked, and felt, in Glasgow, Scotland, two years ago, when she broke Simpson’s steeplechase record and emerged as a legitimate Olympic medal threat, if not a favorite. Ponytail swish, whip the left leg back, swish, right leg back, swish—(hurdle) gliiiiide—swish, whip, swish, whip. Record. Arms in the air, smile for the crowd.

Coburn’s march toward Simpson’s 9:12.50 mark, set in 2009, was methodical and ruthless. In her 2014 season debut in Shanghai, she demolished a field that included all three reigning world championship medalists with a four-second PR of 9:19.80. Thirteen days later at the Prefontaine Classic she ran a 9:17.84 and followed that up a few weeks later with her third national title. Eight days after that, she slashed her PR to 9:14.12 in Paris. There, with the record in play heading into the bell lap, she finally cracked and slowed down. “I couldn’t hear anything anymore except my breath,” she says. “From head to toe, I was tingling. I was at my max.”

Coburn, ever composed, viewed the huge PR despite losing steam as another sign of the inevitable. Exactly a week later she ran a 9:11.42 in Glasgow. History. Or so she thought.

“I love going fast,” Jager says. “I’ve noticed that.”

So did Joel and Cathy Jager, his parents, years ago while watching little Evan exhaust the rest of the kids on the soccer pitch. “It’s one of those things, you’re watching him, you’re going, All right, he’s better at running than the other kids,” Joel says. “I wouldn’t say he was the better soccer player, but he was better at running. He was always able to catch up to the ball.”

Every Friday and Saturday night in middle school, Evan would take his obsession with speed to the local roller rink; he’d strap on an aggressive pair of skates and get a rush, he says, from “just blowing past people.”

Then he discovered that the biggest adrenaline surge came from just plain running. The summer before seventh grade, the Jagers were visiting Joel’s parents out in rural Michigan. “He was really antsy one night,” Joel says, so he and his son went for a walk. The next street was a half mile away, and Joel challenged Evan to run out and back; he’d time him on his watch. Evan returned 6 minutes and 12 seconds later. Not bad for a 12-year-old, over hills and gravel. Joel asked his son how fast he thought he could do it with a little more training, and Evan replied with his trademark confidence: “Five minutes.”

“When you run that I’ll buy you a 5-liter Mustang,” Joel said. “Five-point-oh for a five-point-oh.” Evan did it during the next track season and Joel held up his end of the bargain—though the car would sit in the garage for three years until Evan could drive.

At Jacobs High School in the Chicago suburb of Algonquin, Evan exhibited an almost insatiable desire to run—and win—at any event he could. He claimed state titles in cross country, the 1600, and the 3200, and he anchored a record-setting 4x800 relay team. He ran the 4x400 once and even gave the high jump a try: 5 feet 10 inches at practice for fun. He attended Jerry Schumacher’s summer running camp at the University of Wisconsin the summer before his sophomore year, but it wasn’t until a year later, after he’d had a growth spurt of four inches, that he caught the esteemed coach’s attention.

Jager wound up earning a scholarship to run for Schumacher at Wisconsin, but at the end of his freshman year, just as he was settling in, he faced a dilemma: Schumacher was leaving to launch a pro group with Nike in Portland. “I knew after college I wanted to run professionally with Jerry,” Jager says, “so it was either ‘I’m going to continue running for you and move out to Portland’ or ‘I’m going to stay in college for three or four more years and then run for you.’”

In Jager’s mind, it wasn’t about whether he was good enough to turn pro at 19; he demonstrated as much that summer by placing eighth in the 1500 at Junior Worlds. It was about weighing the opportunity it presented against the forfeiture of his NCAA eligibility and the safety net of the Midwest. He knew his destiny was as a pro runner. “Oh, I have no clue,” he says when asked what other career path he could have taken, shaking his head. “Seriously.”

Jager made up his mind to follow his coach and hired Tom Ratcliffe, his agent to this day. Schumacher worked with Jager’s parents to ensure that he would continue his education at Portland State (where he finished a degree in health studies last year) and that he had the proper support system around him. Joel Jager didn’t mince words with the coach and agent: “You guys have to be his parents.”

Jager’s bet on himself paid off. In the spring of 2009 he placed third at USA Outdoors in the 5,000 meters, earning him a spot on the national team for the world championships at 20 years old. “It was a validation point for him,” Schumacher says. “He believed in himself and what he could do and made it happen.”

Everything was falling into place until June 2010, when Jager fractured the navicular bone in his right foot during the 1500-meter prelims at the 2010 U.S. championships. Surgery and six months downtime followed—the longest layoff of his career. He was miserable, rehabbing on the bike while having to watch his teammates train without him. “All I wanted to do was go for a run,” he says.

As he healed, he and Schumacher and Pascal Dobert, a former Olympic steepler who joined Schumacher’s staff in 2009, discussed a new event, one Jager had been curious about adding to his repertoire and that his coaches thought might be the perfect outlet for his springy athleticism: the steeplechase. The seed had actually been planted years before, in high school, after Jager toyed with the high jump and an assistant coach suggested that he should one day give steeple a try.

“Even when I was younger I was a very bouncy runner,” Jager says. “It was always in the back of my mind as something I thought I might be good at. It looked fun, looked challenging.”

Of all the events to try after coming back from a serious foot injury, though, was the one designed to slowly grind your lower body into bonemeal really the best choice? Jager called his surgeon, Dr. Robert Anderson. “Is this stupid?” he asked. “Are we being foolish?”

“Those two screws are in there holding everything together,” Dr. Anderson told him. “That should be no problem.”

Empowered by his doctor and with a clean bill of health, Jager competed well in the 1500 in 2011 while beginning to covertly work with Dobert. “He took to it like a fish to water,” Dobert says.

The coach says this in earnest, though to hear Jager tell it, he had to do his fair bit of flopping around. The water jump, he says, was “by far” the hardest adjustment. “It took me a long time to trust my foot and trust my body to really take the impact of the water jump.”

Jager made his steeplechase debut at Mt. SAC in April 2012 and wowed onlookers by running an 8:26.14, good enough for the Olympic B standard and, even better, he avoided a splashdown. That dry streak ended at one. A couple weeks later at the Oxy High Performance meet, he took a strong lead well into the last lap, only to blow it by crashing in the final pit. “My foot just went straight into the deep end,” he says, “and I went shoulders-down into the water.”

Jager nonetheless wobbled to his feet—unhurt—and auspiciously sprinted to the finish, earning a time of 8:20.9 and the Olympic A standard. Properly hazed, Jager spent the following weeks working on running cleanly out of the pit “without babying the landing,” he says, and a month later he won the Olympic Trials in 8:17.40. “It just clicked for me,” he says. “I made a huge step in trusting myself and taking the jump efficiently. I felt totally comfortable.”

A few weeks later, in Monaco, he shocked the world by running 8:06.81, a new American Record. It was his fifth steeplechase. “More than anything,” Jager says, “it proved to people what I already thought about myself.” The steeplechase favors the bold, after all. Jager rode that wave out of Monaco and into London, where, at 23, he was the top American in the Olympic final, finishing sixth. He was just getting started.

Coburn refuses to blame the IAAF officials in Glasgow or even USA Track & Field for her record not being ratified, so allow me to do so on her behalf: They all failed her.

Somebody other than the runner who has just pushed herself to the aerobic brink ought to be the one responsible for shuttling said athlete to drug testing. You would think it’s in everyone’s best interest to make sure this necessary step isn’t fumbled; who doesn’t want to be able to promote a record-breaker?

“It was my responsibility to know, since I chose not to have an agent,” Coburn says, sitting at a table on her sister Gracie’s back patio, a red jacket tugged over her workout clothes. Growing up in the mountains can endow a kid with an independent streak, especially when she’s operating in the shadow of talented siblings.

“I was this scraggly black swan,” she says. “Not coordinated, not good at anything”—at least not compared to Willy, four years older than her, and Gracie, her elder by 18 months. (She also has a younger brother, Joe, now 15.)

“She definitely was a late bloomer,” says her father, Bill. But why try to be good at one thing when you can have fun in everything? Emma’s childhood was defined by being outside: Summers involved hiking 14ers, kayaking, swimming in rivers, shooting guns, and mountain biking, and winters were all about skiing and snowboarding.

She attended tiny K-12 Crested Butte Community School, where she would eventually graduate with the same 19 students who were in her third-grade class. Bill and his wife, Annie, expected Emma and her siblings to maintain all As and Bs and participate in three sports. By high school she was doing it all: In addition to being in the National Honor Society and student council, she competed in cross country, volleyball, basketball, and track. In the fall she would go straight from volleyball practice to the cross-country course. “I’d be in school from 7:30 to 7:30,” she says.

She regretfully gave up hockey, her first love, in her freshman year because the boys—she always played with the boys—had gotten so big that a hard check might jeopardize her other pursuits. Her childhood heroes had not been Steve Prefontaine or Joan Benoit Samuelson, but the 1980 U.S. Olympic Hockey team. “I loved the story, their heart and their fight and their spirit,” she says. “I think that competitive side, never thinking you’re out of it, that just seeped into my athletic career.”

It was her sophomore year, with Emma beginning to come into her own as a runner, when it was all nearly snatched away. Bill had taken Emma and a few of her friends out to the family cabin in the ghost town of Tin Cup, when the chimney caught fire in the middle of the night. Bill woke up to a strange crackling sound and realized the cabin was burning. He saw that Emma’s friends had already run out the front door and he sprinted to her room upstairs. Choking on smoke, he ran back outside to catch a breath and heard one of the girls yell, “She’s out back!” Disoriented by carbon monoxide poisoning, Emma had stumbled out the back door. Everyone was safe, but the generations-old cabin would have to be rebuilt from the ground up.

Bill thinks the incident contributed to Emma’s unflinchingly positive outlook. “Until you’ve been on that edge you maybe don’t appreciate things the same,” he says.

Emma finished fourth at state in cross country her junior year and discovered the steeplechase by accident during track season. Traveling to Albuquerque to run an 800, Emma and Bill decided to make the most of the trip and sign her up for a steeple. After asking race officials how many laps there were, she won in a nationals-qualifying time. She’d place fourth in the steeplechase at Nike Outdoor Nationals, where she introduced herself to Wetmore in the parking lot. “She had to be a pretty self-confident 16-year-old to do that,” he says.

It helped that from that very first race in Albuquerque, Coburn felt natural competing in what is for many runners a most unnatural event. Standing 5’ 8”, Coburn has never been intimidated by the 30-inch barriers—in fact, she found analogs to volleyball and basketball. “When you’re taking the steps before a jump, it’s like going up for a layup or spike,” she told me between pistol squat reps at her local gym. “It’s my favorite part.”

Coburn placed second at nationals her senior year to go with eight state titles, and in the spring of 2008 she secured a scholarship to run for Wetmore at Colorado. That summer she watched the track and field events at the Olympics. In the debut of the women’s steeplechase, she saw rising Colorado senior Jenny Simpson (then Barringer) break the American Record. “I was like, Oh my gosh, she’s gonna be my teammate!” Coburn says.

What was even better: On Coburn’s first cross-country trip that fall, they were roommates. “Mark encouraged the older veterans on the team to shepherd along the freshmen,” Simpson says. The Olympian saw a little of herself in the teenager. “The patience it takes to develop your speed, keep with the barrier work, we were very similar in that way,” Simpson says.

Coburn’s biggest learning curve was adjusting to the pack dynamics of elite-level steeplechases, something she rarely contended with in high school, where talent disparity would often string out races by the end of the first lap. “I remember my first big college race at Mt. SAC feeling a little chaotic,” she says. “It’s hard to have good form when you’re stuck in a big pack or don’t have a clear view of a water jump. You may never have a clear view of a barrier in a race.” It’s a discomfort she says that only experience can help ease, and something that even now takes a few laps to shake off at the beginning of every race season.

Coburn would take up Simpson’s steeplechase mantle, but only after her elder claimed another NCAA title and lowered the American Record by an unthinkable 10 seconds, to 9:12.50 at the Berlin World Championships, where she placed fifth. Simpson, though, would be destined for greatness in another event, the 1500.

Coburn won the NCAA and U.S. steeplechase titles her junior year, and redshirted her senior season of track to focus on the Olympic trials—which she also won. In London, she placed ninth in the final, running a 9:23.54 PR that left only Simpson ahead of her in the record books. Just as everything appeared to be lining up, same as with Jager, injury struck: During the 2013 NCAA championships she suffered a sacral stress fracture. Somehow, adrenaline helped her push past the pain she felt on every jump in order to win the race, but she was devastated. “I was trying to sign a contract,” she says. “I was trying to break the NCAA record. I had all of these hopes and realistic expectations.”

Coburn’s 2013 season was shot, but New Balance signed her anyway—a show of support that won the young runner’s intense loyalty. (She makes a point of taking me to New Balance’s splashy new Run Hub in Boulder during my visit.) She wouldn’t race again for eight months but would return in 2014 healthier—and hungrier—than ever.

Jager’s teammates like to tease him for his celebrity status. After their morning long run, he and Lopez Lomong and Ryan Hill jog over to Nike’s brick-red practice track, hidden amid a thicket of pines, for some stride work. Jager sheds a blaze-orange tech tee, revealing a bold tattoo of the Olympic rings running vertically along his right torso from his hip to his armpit. Hill leans over to me as I jot down notes from the morning session and dictates, “Jager, the only one working out shirtless…”

Dan Huling, one of the top-notch steeplers Schumacher has assembled around Jager, says they refer to him simply as “the American.” Over the phone a few weeks later, Huling explains by affecting broadcaster Tim Hutchings’s British accent: “Then the American”—the implication being that Jager is so often the only American near the front of international steeplechases that he can be identified solely by his nationality.

That may not be the case for long. Jager preaches the value of being able to train alongside the likes of Huling, a veteran of three U.S. world teams, Canadian steeplechase record holder Matt Hughes, and the raw-but-gifted Andy Bayer—and the benefits cut both ways. Huling and Bayer rode Jager’s aggressive pace at USAs last year to third-and fourth-place finishes; that single race had four men crack 8:22 (the other being Donn Cabral). “Anytime someone really, really good comes into an event, someone like Evan,” Huling says, “it’s gonna up what’s going on behind you.”

Which brings us to the Worlds in Beijing last August, where Jager placed sixth—a bigger disappointment, he says, than the fall in Paris. “That stuck with me longer.”

Jager is a wild stallion—a mustang—who yearns to run free. The claustrophobic pack dynamics and slow burn of championship races have tested this instinct, as they have with Coburn. “It’s like driving on a highway with a lot of traffic but no lanes, and trying to move in unison with all these other cars,” he says. “It’s very uncomfortable.”

It’s what sets the steeplechase apart from the sprint hurdles (other than it being a distance race)—there are no lane designations to harness the inherent danger of a group of athletes sprinting and jumping over things as fast as they can. Guys in the 400-meter hurdles, for instance, “know what 17 steps or 15 steps feels like…it’s just an ingrained rhythm in their brains,” Jager says. “In the steeple, I don’t think anyone counts steps. It’s just way too much.” Coburn occasionally commiserates with elite hurdlers at international meets (usually to gush over their precise form), and an exchange she once had with Olympic champion Dawn Harper-Nelson sums up how the dissimilar specialists in these two events view each other: “I’m so glad I’m not a 100-meter hurdler,” Coburn said. “I’m so glad I’m not a steeplechaser!” Harper-Nelson replied.

Amid the pack in Beijing, Jager ran with agitation. He tucked in near the front for two kilometers until he couldn’t take it anymore and moved abreast of the leader, Conseslus Kipruto, with whom he was neck-and-neck going into the bell lap. Then, around the last curve, the four Kenyans in the race surged past him and he had no chase left. The exuberant Ezekiel Kemboi pranced across the line for his sixth global title in 8:11.28, which Jager had already bested seven times in his career. A flash of red also passed him in the last 100 meters—his training partner Huling, who at 32 had just run the race of his life. “I was obviously elated,” Huling says, “but I had to temper my own emotions to help out Evan.”

As they traveled to Zurich for a meet the following week, the elder steepler gave his younger, faster teammate some advice: Be patient. Huling learned it the hard way after falling short of his Olympic dream in 2008 (fifth at the Trials) and 2012 (seventh); now, partly because of Jager, his best shot awaits him in Eugene. “It doesn’t happen all right away,” Huling told him. “This hurts, but wouldn’t you rather go through it now, learn from it, and then medal next year?”

It’s another learning experience for Jager; he’s proven his worth but knows that in order to be considered truly great, he has to solve tactical championship brawls. It’s a challenge he embraces: “You should have to win the race on that day to be crowned champion.”

Jager legs out his last stride on the Nike track, pulls his shirt over his mop of hair, and waves for me to follow him. As he jogs into the trees, he passes Alberto Salazar and his star pupil, Olympic 10,000-meter silver medalist Galen Rupp, who are getting ready for their own track session. Salazar’s Nike Oregon Project and the Bowerman Track Club share many facilities, and exchanges between members of the frenemy groups, at least during my visit, ranged from genuinely warm to “workplace-polite.” Salazar and Rupp both reciprocate Jager’s smile and head nod. Game recognize game. In Rio, after all, they’ll be on the same team.

“There have been times that I’ve told someone I do the steeplechase,” Coburn says, “and people assume it’s equestrian.”

She sits up on her kitchen counter in her apartment on a Sunday morning, post-long run, spooning sliced mango, Greek yogurt, and maple syrup out of a bowl. Her corner unit faces to the southwest, and behind her looms a spectacular view of the mountains. Her bare feet dangle, showing off an Olympic rings tattoo on her right foot.

To be sure, steeplechase has historically been an outsider’s event. Both Coburn and Jager bristle, however, at the old stigma that it’s where coaches stick runners who aren’t very good at the 1500 or 5,000. “I think that mentality needs to disappear,” Jager told me, irritated at the suggestion.

“Evan was briefly ranked No. 1 in the world in the 1500 last year,” Coburn points out. And there’s the example of her friend and mentor, Simpson, who is one of the best 1500-meter runners in the world.

The event’s appeal to top athletes is growing, especially on the women’s side. Whereas Simpson had to contend with one or two other U.S. women nipping at her heels, a stable of at least a half dozen strong, young steeplers chase Coburn. “You aren’t motivated to run an event that you can’t run in college or the Olympics,” Simpson says. Women’s 3,000 steeple was first held at U.S. nationals in 1999, but its inclusion at the 2008 Games, she says, “was really necessary for it to attract the best talent.”

What didn’t help were the two doping bombshells that dropped last year: 2009 world champion Marta Dominguez of Spain and 2011 Worlds and reigning Olympic champ Yuliya Zaripova of Russia were both sanctioned for failed tests and stripped of their medals. “In my head, there are athletes who when they do a crazy performance I’m like, eye roll, that’s not real,” Coburn says. “I blur those times out and I scroll down to the first clean athlete I believe in. That’s how my brain works.”

The steeplechase is hard enough without having to incorporate such mental gymnastics, but Coburn is resigned to the reality that beyond being a vocal advocate for clean sport, there’s not much she can do about it.

Coburn entered 2016 focusing on lessons learned in 2015. She fell short of her goal to PR—and “officially” claim the record—though her season best of 9:15.59, which won her her fourth USA title last June, made her the sixth-fastest woman in the world. Nothing to sneeze at. A nagging Achilles injury slowed her at times last year, but at the World Championships in Beijing she expected to medal. Coburn, well known for front-running, opted for a sit-and-kick strategy. She took the lead with two laps to go but could never gain separation, and faded to fifth place.

Coburn has no regrets. “In 2014 I didn’t care as much about the win—it was about time, and pushing hard,” she says. “Last year was more about place and trying different racing strategies.” She didn’t race indoors this year, and came into the spring focused on getting healthy, piling on the miles, and upping her fitness. “I’m hoping to be perfect in August—at times I’ve been a little too perfect in June,” she says.

Nobody was more shocked than Coburn when, in her season debut at the Prefontaine Classic in May, she finally earned her official American Record. Following the blistering pace set by Ruth Jebet, who would become the second woman to break 9 minutes in history, and Hyvin Kiyeng, just milliseconds behind in second place, Coburn sailed to a 9:10.76 finish, bettering her mark from Glasgow. She promptly found her way to drug testing and sealed the deal with a tweet: “Drug test done. #AmericanRecord.”

“Leading up to Pre I had had good workouts and felt like I was in really good shape, but I wasn’t expecting that,” Coburn says. “It is definitely satisfying [to officially get the AR] and in some regards even more satisfying than the first time around.”

If she makes it to Rio, she’s not yet sure how she’ll run it—the steeple at Pre affirmed that her international competition is as fierce as ever—but she knows exactly how she’ll be measuring success. “People say records are broken all the time, and running fast times is exciting,” she says, “but medals you get to keep forever.”

Aside from getting to train and race in exotic locales, professional runners lead boring lives. Most happily admit this. We hoi polloi are supposed to treat our bodies like temples; it stands to reason, then, that those whose livelihoods depend on physical fitness must operate like ascetics. Which is what makes this last story so refreshing.

It’s August 6, 2012, night falling over the Olympic Village. Spots of rain have washed away the sweat of competition, giving the mild London evening an air of rejuvenation. Coburn and Jager have been texting. After exceeding all expectations in their Olympic debuts, it was time the two steeplechase prodigies finally got to know each other.

The night involved an entourage that included, at various points, Jager and Coburn; Coburn’s boyfriend, Joe Bosshard; her brother and sister; and a couple of Australian comrades. The night started at the casino bar next door, which had become a popular athlete escape from the cloister of the Olympic Village.

It had been a long week—no, a long year. The pressure of the Summer Olympics builds and builds until erupting like a whistling kettle in the penultimate month. After allowing her 21-year-old self to enjoy the spectacle of the Opening Ceremonies, Coburn had soberly wrestled that wonderment into submission long enough to advance out of her heat and run a PR in the final. Jager, only 23, had finished sixth in his final yesterday. Yes, it was time for a drink. A few drinks.

Eventually the group leaves the casino bar to peruse the adjacent mega-mall. Questionable purchases are made: Justin Bieber and Prince Harry masks; a can of energy drink Coburn is convinced is labeled “Emma-rgy.” (She’ll look at it tomorrow and mutter, “That just says Emerge.”) Later they find themselves in the Tube station beneath the mall and encounter underground roller-bladers, where Jager will fight the temptation to relive his heyday as an Algonquin rink god. At some point—memories are foggy—they emerge from the subterranean playplace and return to their rooms to sleep off the buzz of their first Olympics. When they wake up, Coburn and Jager will go on respective training runs, taking the first proverbial steps toward Rio. Back to work, as if the bar and the masks and the skaters never existed.

In four years, they know, there will be no sneaking up on anyone. Making the finals will not be a pleasant surprise. In four years there will be Expectations.

Yes, Coburn and Jager aspire to medal in Rio, and it isn’t fantasy for the rest of us to picture them both in gold. They have proven time and again that they can contend with the world’s top steeplechasers. They both embrace the pressure of being heavy favorites in this year’s Trials, but know better than to take any race lightly. “Everyone’s days are numbered,” Jager says.

“No one is safe,” says Coburn.

That they understand the risks and proceed anyway makes them all the more dangerous. The kids are all grown up, yet they remain fearless. Giddy-up.