Rachel Schneider, a professional middle-distance runner in Flagstaff, Arizona, who recently set a new indoor mile personal best of 4:25.62, catches herself talking about a road trip up the West Coast with one of her best friends. Maybe they’ll go to Glacier National Park, then up to Banff?

She laughs at the level of detail she’s already considered because the trip won’t happen for another seven months, and she has a lot to accomplish between now and then. But daydreaming about an upcoming adventure makes the focus on a performance-oriented lifestyle more manageable. Choosing the right foods, getting to bed early, preparing for arduous workouts, lifting, stretching, cross training, and logging lots of miles are all critical parts of a routine that Schneider, 25, has joyfully chosen in order to become a better runner. But taking a break from the hypervigilance now and then is just as crucial to her success, she says.

While you might not approach your running with Schneider's intensity, the principle is the same: taking time away from running helps your long-term success.

“I really only take one big break every year, in the second half of September after the outdoor track season is over,” Schneider says. “My coach and I agree to not talk for a few weeks. I go be a ‘normal person,’ relax, and have fun. It’s a complete mental and physical reset and makes me excited to start training again.”

Breaks come in various forms. Planned breaks, like the ones that Schneider enjoys, are the best kind. Unplanned breaks forced by injuries, illness, and other unforeseen circumstances are less desirable and sometimes preventable with strict adherence to the former variety. For elite athletes, the natural breaks come at the end of competitive seasons. For recreational runners, they can be planned after big goal races or times that are convenient for work and family.

“It’s kind of like a checkpoint, or a finish line of sorts,” says Kyle Merber, 26, a member of the New Jersey-New York Track Club whose 2017 indoor season was highlighted by placing third in 3:54.67 at the Millrose Games Wanamaker Mile. “When you’re in the middle of training you can look to it and say, ‘All I have to do is survive another month.’ It makes it a little easier to wrap your mind around the training.”

Here’s how to make the most of your breaks, in whatever form they come:

Unplug. Schneider loves the outdoors, but peak training leaves little time or energy to go camping—or trek along technical trails that are riddled with opportunities for injury. So, the two weeks she takes off from running in September are usually dedicated to big hiking trips. Her favorite so far was in 2016, when her sister and father were hiking the John Muir Trail in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. She joined them for the last five days for about 65 miles.

“Being in the mountains with no technology for five days was amazing,” she says. “It was so good to be completely in nature with my dad and sister, exploring a beautiful part of the country. I loved not having to think about how everything impacts me physically and just enjoy it.”

Stay in touch with some exercise. Merber usually heads out in September, after the Fifth Avenue Mile, for two or three weeks on a vacation with his college buddies. They’ve gone to New Zealand, Australia, and Southeast Asia, to name a few destinations. He’s tried leaving his running shoes at home during his journeys, but found that his body doesn’t respond well to going cold turkey, so now he incorporates easy 30– to 40-minute jogs into his sightseeing during the second and third weeks of his break.

“I found that if I didn’t run at all, when I got back to it I’d get injured,” Merber says. “It’s unstructured. I don’t consider it training—it’s exploring along the beach with no plan in mind whatsoever. I think it allows my body to stay healthy and not too far removed from the act of running.”

Indulge. Although Schneider doesn’t deprive herself of most foods or the occasional glass of wine during the season, it’s liberating to go out late with friends without suffering severe repercussions during her run the next day.

“It’s a time that I just really don’t pay attention to what I’m eating or when I’m going to bed. I can justify an extra piece of cake or a couple of more drinks than usual,” she says.

Beyond “exploring the nightlife like a normal 20something,” Merber really enjoys not needing to sleep quite as much.

“The only reason I ever get nine hours of sleep is because of running,” he says. “I really enjoy existing on five hours and being able to see the majority of the day.”

Make the most of it. Four-time Olympian Shalane Flanagan, 35, recently learned that a fracture in her iliac crest in her pelvis would require up to six weeks of rest, keeping her out of the 2017 Boston Marathon, where she holds the American course record of 2:22:02. It’s not the kind of running vacation she wanted, but after the initial sting she started to see some opportunities in the forced time away. She took a spontaneous trip to Bend, Oregon, to visit her best friend, Elyse Kopecky, with whom she coauthored a cookbook, Run Fast, Eat Slow, last year.

“We’re starting another project…It’s always good to have other things to focus on,” Flanagan says. “Spending time with her is much needed.”

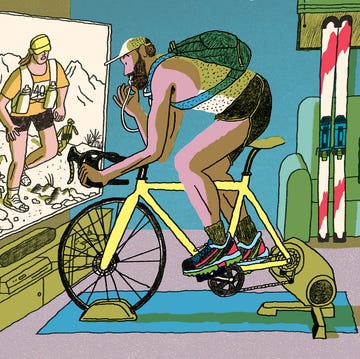

Flanagan has also embraced the opportunity to try other forms of exercise while she’s healing. She grew up as a competitive swimmer and is putting in lots of laps during her break.

“I’ve done so much running in my lifetime, it’s kind of fun to do something different,” she says.

Get antsy. You’ve done the break right when you can’t wait to start running again. Merber knows exactly when it’s time to go back to his routine.

“It’s when I look myself in the mirror and I’m like disgusted with who I’ve become,” he says, laughing. “It’s just when you’re excited to do it and you’ve gotten everything out of your system.”

Schneider knows it’s time to start training again when she feels the itch to start doing some short, easy jogs. It’s a natural progression from there—she’s feeling mentally refreshed, but not too far gone physically.

What does getting back to training entail? For Merber, “it comes with lots of salads and if I did the break well, it surprisingly doesn’t take that long.”