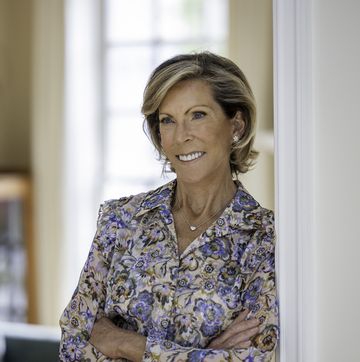

Samantha Mixon was 33 in March 2012 when she began having headaches. Her doctor diagnosed them as migraines and prescribed pain pills. When she temporarily lost her vision, twice—she had no depth perception and saw swirly colors—ER doctors at the hospital told her that her migraines were probably related to a sinus infection.

"They told me to take Mucinex. I could blow my nose 100 times; it wasn't draining. Nothing was working," says Samantha, a mother in St. Simon's Island, Georgia. "I even got a nebulizer, because I felt like there was something in my chest."

Five months later, in August 2012, the soreness in her back started. She thought she'd pulled a muscle, and her doctor gave her muscle relaxants to help with the pain. None of the pills helped.

MORE: What You Need To Know About The Number One Cancer Killer Of Women

A shocking diagnosis

On the Sunday before Thanksgiving 2012, Samantha was reading her then 7-year-old daughter a book in bed. "I coughed and I thought it was phlegm," she says. "But when I spit it out in the bathroom, it was actually blood. I knew that wasn't good."

After Thanksgiving, Samantha visited her family in Atlanta. "My sister started accusing me of being a drug addict because I was taking pills every three hours," she says. "She and I got into it big time, then my parents got into it. That was when I said, 'I need to go to the hospital. I think my world is coming to an end. I'm dying here.'"

Her mother drove her to the local hospital, where an MRI uncovered a grey area in her brain. It was a tumor. Samantha was immediately transferred to a larger hospital that could remove it. "I insisted that they bring me my daughter just as they were putting me in the back of ambulance," she says. "I wanted to see her one last time, just in case something happened. She wanted to go with me. I hugged her, told her it was going to be OK, and I loved her." Samantha says her daughter understood she was going to get a tumor removed, and she was terrified her mother was going to die. "She didn't sleep all night," says Samantha. "She just stayed up and stared at my dad."

"Had I had that brain tumor a few more weeks, I would have died."

The doctors waited until Tuesday for the swelling in her brain to go down before Samantha underwent emergency surgery. "Going in to the surgery, I wasn't too worried," she says. "My cousin and my aunt had brain tumors and they were all benign. I thought I just had a brain tumor. I'd have it removed and it'd be OK. I was really not expecting cancer."

After surgery, her neurosurgeon explained he was able to remove all of the tumor—but it was malignant. And it came from somewhere else in her body, most likely her lung. "That was very hard to process," says Samantha. "I just knew it was stage IV cancer, because it came from another organ."

Samantha later woke to her mom, dad, and friends all by her bedside, crying. After further tests, her oncologist confirmed that she had stage IV lung cancer—and she had 12 to 18 months to live. "The area that was hurting on my back was exactly where my primary lung cancer tumor was," she says.

When visiting hours were over that night and everyone left the room, Samantha had a conversation with the neurosurgeon's assistant that forever changed the way she looked at her diagnosis. "She told me, 'Samantha, you're 33 years old. Don't give up, you can do this. You have an advantage, most people don't get lung cancer at 33, but anyone can get it,'" says Samantha. "She gave me hope. She said, 'Don't listen to the statistics. That's the average cancer patient. Not you.'"

MORE: "I Have PTSD After Surviving A Brain Tumor—But Running Helps Me Cope"

The 'lottery of lung cancer'

Given her new diagnosis, Samantha was transferred to MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where she underwent more tests. Initially, doctors planned to remove just her right lung—until they discovered that the cancer had spread to her left lung. At the same time, more tests also uncovered what turned out to be hopeful news: Samantha had the EGFR mutation.

"I won the lottery of lung cancer, I think, because there were drugs that were targeted for my type of mutation," says Samantha, who had non-small cell lung cancer—with a genetic mutation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). According to CancerCare, a national nonprofit, that mutation means she produces too much EGFR protein, a normal substance that helps cells grow and divide, so her cells grow and divide too quickly. The lucky part? Unlike other cancers and mutations, there is a targeted and potentially effective treatment for the EGFR mutation. Drugs known as EGFR inhibitors block the EGFR receptors on the cell surface, slowing or stopping the growth of the cancer. Doctors put Samantha on one of these drugs.

"I just knew it was stage IV cancer, because it came from another organ."

"It recognizes the mutation in my DNA, so I don't get nearly the side effects I'd get on chemo," says Samantha. "But I have to take it once a day for the rest of my life. And, eventually, it will stop working."

While Samantha's survival rate changed with her new diagnosis and doctors told her the medicine had a high success rate at stopping or regressing the tumor's growth, they didn't give her a new timeline. "They didn't tell, I didn't ask," she says. "I was afraid of the answer."

Getting support

"I was very depressed the first year of my diagnosis," says Samantha. "In the beginning, I had no hope."

In the nearly 4 years since then, Samantha, now 36, says she's become much more hopeful. Antidepressants helped, as did her support group. And she gets a lot of support through a Facebook page with a couple hundred survivors of the same type of cancer. "I came across survivors who have been on this drug for years," she says.

She also became involved in her church and now prays every day. "I know everything is not in my hands, so I just let go of the worry," says Samantha. "I've realized it's not worth worrying about things that are out of your control. That will just make your life worse."

Even her family has gotten used to the new normal. "In the beginning, they wanted me around all the time," she says. "They got so weepy-eyed, and I could do no wrong. Now it's back to old ways, like I don't even have cancer. Sometimes I even forget I have cancer."

After the diagnosis, Samantha's daughter insisted on sleeping in Samantha's bed every night—for 2 years. "At one point, I asked her why," says Samantha. "She told me, 'just in case you die during the night.'" Because she was a single mom at the time and they were the only two people in the house, Samantha showed her daughter how to call 911, just in case. She also took her daughter to therapy.

In April 2015, Samantha met the man who would become her husband when she moved across the street from him. "Our daughters already knew each other, but we didn't," she says. "I told him about my cancer diagnosis as I was moving in. Then I got pneumonia and was unable to move the rest of my stuff. He went and got it for me, picked up my prescriptions, and cooked me dinner each night. The fact that I had lung cancer didn't bother him." The couple married this March. "He always takes care of me now," she says.

"I've realized it's not worth worrying about things that are out of your control."

At Samantha's last PET scan in September, doctors found she still has two tumors and a nodule in her lungs—but no active cancer. "They can wake up any day when the medicine quits working," she says. "But right now, they're not waking up. So I'm just trying to stick to everything I'm doing, because it's working."

Samantha says she has on and off days. She spends time with her now 11-year-old daughter and 12-year-old stepdaughter, especially on weekends, and takes care of household chores throughout the week. But sometimes her target therapy pill knocks her out. "It's like I have to head to bed right now," she says. "When my body tells me I need to sleep, I go to sleep. I nap every day now."

MORE: "My Mother, Aunts, And Grandmother All Had Breast Cancer—Now I Have It, Too"

Finding a cure

To other women who have been diagnosed with cancer, Samantha says to remain positive. "Believe the diagnosis, not the prognosis," she says. "Every diagnosis is different."

Samantha now volunteers at the American Lung Association's advocacy group LUNG FORCE, because she hopes to help take the stigma out of lung cancer. "I was embarrassed at first, because when people think of lung cancer, they think of a smoker," she says. "But that wasn't me. They think of an old person, and that wasn't me either. I thought maybe, if I shared my story, it would encourage other people to come out, too. Because anyone can get it."

According to LUNG FORCE, two-thirds of lung cancer diagnoses are among people who have never smoked or are former smokers. And it's the number one cancer killer of women. In 2016, it's estimated that more than 106,000 American women will be diagnosed with the disease. Survival rates are about five times lower than other major cancers, with a five-year survival rate of only 18%. An estimated 72,000 American women will die this year of lung cancer—more than a quarter of all cancer deaths among women.

Despite these sobering stats, unlike other cancers, lung cancer remains a bit taboo. A recent survey of more than 1,000 American women by LUNG FORCE found that less than half of those who are considered high risk for lung cancer have spoken to their doctors about it. What's more, in part because only people at high risk can be screened for lung cancer in the first place, 77% of women are diagnosed with lung cancer in later stages—when it's harder to treat. By telling her story, Samantha hopes to change some of these statistics.

"I want to stop the stigma," she says. "If you have lungs, you can get lung cancer."

This story was originally published by our partners at WomensHealthMag.com.