1901-1971

Who Was Louis Armstrong?

Jazz musician Louis Armstrong, nicknamed “Satchmo” and “Ambassador Satch,” was an internationally famous jazz trumpeter, bandleader, and singer. An all-star virtuoso, the New Orleans native came to prominence in the 1920s and influenced countless musicians with both his daring trumpet style and unique vocals. He is credited with helping to usher in the era of jazz big bands. Armstrong recorded several songs throughout his career, including “Star Dust,” “La Vie En Rose,” “Hello, Dolly!” and “What a Wonderful World.” Ever the entertainer, Armstrong became the first Black American to star in a Hollywood movie with 1936’s Pennies from Heaven. The legendary musician died in 1971 at age 69 after years of contending with heart and kidney problems.

Jump to:

- Who Was Louis Armstrong?

- Quick Facts

- When Was Louis Armstrong Born?

- Musical Beginnings

- Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five

- Famous Louis Armstrong Songs

- "What a Wonderful World"

- Satchmo in Movies and Music Career Turbulence

- Louis Armstrong and the All Stars

- Wives

- Alleged Daughter Sharon Preston-Folta

- Ambassador Satch

- Support of the Little Rock Nine

- Later Career: “Hello, Dolly!” and More International Tours

- When Did Louis Armstrong Die?

- Quotes

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Louis Daniel Armstrong

BORN: August 4, 1901

DIED: July 6, 1971

BIRTHPLACE: New Orleans, Louisiana

SPOUSES: Daisy Parker (c. 1918-1923), Lillian Hardin (1924-1938), Alpha Smith (1938-1942), and Lucille Wilson (1942-1971)

CHILDREN: Clarence and Sharon

ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Leo

When Was Louis Armstrong Born?

Louis Daniel Armstrong was born on August 4, 1901, in a New Orleans neighborhood so poor that it was nicknamed “The Battlefield.”

He had a difficult childhood. His father was a factory worker and abandoned the family soon after Louis’ birth. His mother, who often turned to prostitution, frequently left him with his maternal grandmother.

Armstrong was obligated to leave school in the fifth grade to begin working. A local Jewish family, the Karnofskys, gave young Armstrong a job collecting junk and delivering coal. They also encouraged him to sing and often invited him into their home for meals.

Musical Beginnings

On New Year’s Eve in 1912, when Armstrong was 11 years old, he fired his stepfather’s gun in the air during a celebration and was arrested on the spot. He was then sent to the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys. It proved to be a pivotal time in his life. There, Armstrong received musical instruction on the cornet and fell in love with music. In 1914, the home released him, and he immediately began dreaming of a life making music.

While he still had to work odd jobs selling newspapers and hauling coal to the city’s famed red-light district, Armstrong began earning a reputation as a fine blues player. One of the greatest cornet players in town, Joe “King” Oliver, began acting as a mentor to young Armstrong, showing him pointers on the horn and occasionally using him as a sub.

In 1918, Armstrong replaced Oliver in Kid Ory’s band, then the most popular band in New Orleans. He was soon able to stop working manual labor jobs and began concentrating full-time on his cornet, playing parties, dances, funeral marches, and at local honky-tonks, a name for small bars that typically host musical acts.

Beginning in 1919, Armstrong spent his summers playing on riverboats with a band led by Fate Marable. It was on the riverboat that Armstrong honed his music reading skills and eventually had his first encounters with other jazz legends, including Bix Beiderbecke and Jack Teagarden.

Influencing the Creation of the First Jazz Big Band

Although Armstrong was content to remain in New Orleans, in the summer of 1922, he received a call from Oliver to come to Chicago and join his Creole Jazz Band on second cornet. Armstrong accepted, and he was soon taking Chicago by storm with both his remarkably fiery playing and the dazzling two-cornet breaks that he shared with Oliver. Armstrong made his first recordings with Oliver on April 5, 1923; that day, he earned his first recorded solo on “Chimes Blues.”

Lillian Hardin, the band’s female pianist whom Armstrong married in 1924, made it clear she felt Oliver was holding Armstrong back. She pushed her husband to cut ties with his mentor and join Fletcher Henderson’s Orchestra, the top African American dance band in New York City at the time.

Armstrong followed her advice, joining Henderson in the fall of 1924. He immediately made his presence felt with a series of solos that introduced the concept of swing music to the band. Armstrong had a great influence on Henderson and his arranger, Don Redman, both of whom began integrating Armstrong’s swinging vocabulary into their arrangements. The changes transformed Henderson’s band into what is generally regarded as the first jazz big band.

However, Armstrong’s southern background didn’t mesh well with the more urban, Northern mentality of Henderson’s other musicians, who sometimes gave Armstrong a hard time over his wardrobe and the way he talked. Henderson also forbade Armstrong from singing, fearing that his rough way of vocalizing would be too coarse for the sophisticated audiences at the Roseland Ballroom. Unhappy, Armstrong left Henderson in 1925 to return to Chicago, where he began playing with his wife’s band at the Dreamland Café.

Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five

While in New York, Armstrong cut dozens of records as a sideman, creating inspirational jazz with other greats, such as Sidney Bechet, and backing numerous blues singers, including Bessie Smith.

Back in Chicago, OKeh Records decided to let Armstrong make his first records with a band under his own name: Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five. From 1925 to 1928, Armstrong made more than 60 records with the Hot Five and, later, the Hot Seven.

Today, these are generally regarded as the most important and influential recordings in jazz history. On the records, Armstrong’s virtuoso brilliance helped transform jazz from an ensemble music to a soloist’s art. His stop-time solos on numbers like “Cornet Chop Suey” and “Potato Head Blues” changed jazz history by featuring daring rhythmic choices, swinging phrasing, and incredible high notes.

Armstrong also began singing on these recordings, popularizing wordless “scat singing” with his hugely popular vocal on 1926’s “Heebie Jeebies.” In 2002, all the tapes were preserved in the National Recording Registry.

The Hot Five and Hot Seven were strictly recording groups, however. Armstrong performed nightly during this period with Erskine Tate’s orchestra at the Vendome Theater, often playing music for silent movies. While performing with Tate in 1926, Armstrong finally switched from the cornet to the trumpet.

Famous Louis Armstrong Songs

Armstrong’s popularity continued to grow in Chicago throughout the 1920s, as he began playing other venues, including the Sunset Café and the Savoy Ballroom. A young pianist from Pittsburgh named Earl Hines assimilated Armstrong’s ideas into his piano playing.

Together, Armstrong and Hines formed a potent team and made some of the greatest recordings in jazz history in 1928, including their virtuoso duet, “Weather Bird,” and “West End Blues.” The latter performance is one of Armstrong’s best known works, opening with a stunning cadenza that features equal helpings of opera and the blues. With its release, “West End Blues” proved to the world that the genre of fun, danceable jazz music was also capable of producing high art.

In the summer of 1929, Armstrong headed to New York, where he had a role in a Broadway production of Connie’s Hot Chocolates, featuring the music of Fats Waller and Andy Razaf. Armstrong was featured nightly on Ain’t Misbehavin’, breaking up the crowds of (mostly white) theatergoers nightly.

That same year, he recorded with small New Orleans–influenced groups, including the Hot Seven, and began recording larger ensembles. Instead of doing strictly jazz numbers, OKeh Records began allowing Armstrong to record popular songs of the day, including “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” “Star Dust,” and “Body and Soul.”

Armstrong’s daring vocal transformations of these songs completely changed the concept of popular singing in American popular music, and had lasting effects on many singers who came after him, including Bing Crosby, Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, and Ella Fitzgerald.

Armstrong’s 1950 recording of “La Vie En Rose” remains one of his most recognizable vocals. It was notably featured on the soundtrack of the 2008 animated film WALL-E. Other popular songs of his included “Swing That Music,” “Jubilee,” “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” and the Grammy-winning “Hello, Dolly!,” his only No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. (The chart began in August 1958, well into Armstrong’s career.)

Like his Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings, Armstrong’s 1938 song “When the Saints Go Marching In” and his jazz transformation of Kurt Weill’s “Mack the Knife” from 1956 were enshrined in the National Recording Registry.

Armstrong and Fitzgerald partnered on a collection of duets and made three albums in the second half of the 1950s. The songs include “Makin’ Whoopee,” “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off,” and “Cheek to Cheek,” originally written for the 1935 film Top Hat starring Fred Astaire. All their duets were released on a four-disc set in 2018 to celebrate Fitzgerald’s 100th birthday.

"What a Wonderful World"

One of Armstrong’s most beloved song is “What a Wonderful World,” which the musician recorded in 1967. Different from most of his recordings of the era, the ballad features no trumpet and places Armstrong’s gravelly voice in the middle of a bed of strings and angelic voices. Armstrong sang his heart out on the number, thinking of his home in New York City’s Queens as he did so.

“What a Wonderful World” received little promotion in the United States. The tune did, however, become a No. 1 hit around the world, including in England and South Africa. Eventually, it became an American classic after it was used in the 1986 Robin Williams film Good Morning, Vietnam.

Satchmo in Movies and Music Career Turbulence

By 1932, Armstrong was known as “Satchmo,” a shortened version of satchel mouth, on account of his large mouth. He had also had begun appearing in movies and made his first tour of England. While he was beloved by musicians, he was too wild for most critics, who gave him some of the most racist and harsh reviews of his career.

Satchmo didn’t let the criticism stop him, however, and he returned an even bigger star when he began a longer tour throughout Europe in 1933. In a strange turn of events, it was during this tour that Armstrong’s career fell apart.

Years of blowing high notes had taken a toll on Armstrong’s lips, and following a fight with his manager Johnny Collins—who already managed to get Armstrong into trouble with the Mafia—he was left stranded overseas by Collins. Armstrong decided to take some time off soon after the incident and spent much of 1934 relaxing in Europe and resting his lip.

When Armstrong returned to Chicago in 1935, he had no band, no engagements, and no recording contract. His lips were still sore, and there were still remnants of his mob troubles. His wife Lillian was also suing Armstrong following the couple’s split.

He turned to Joe Glaser for help. Glaser had mob ties of his own, having been close with Al Capone. But he had loved Armstrong from the time he met him at the Sunset Café, which Glaser had owned and managed. Armstrong put his career in Glaser’s hands and asked him to make his troubles disappear. Glaser did just that. Within a few months, Armstrong had a new big band and was recording for Decca Records.

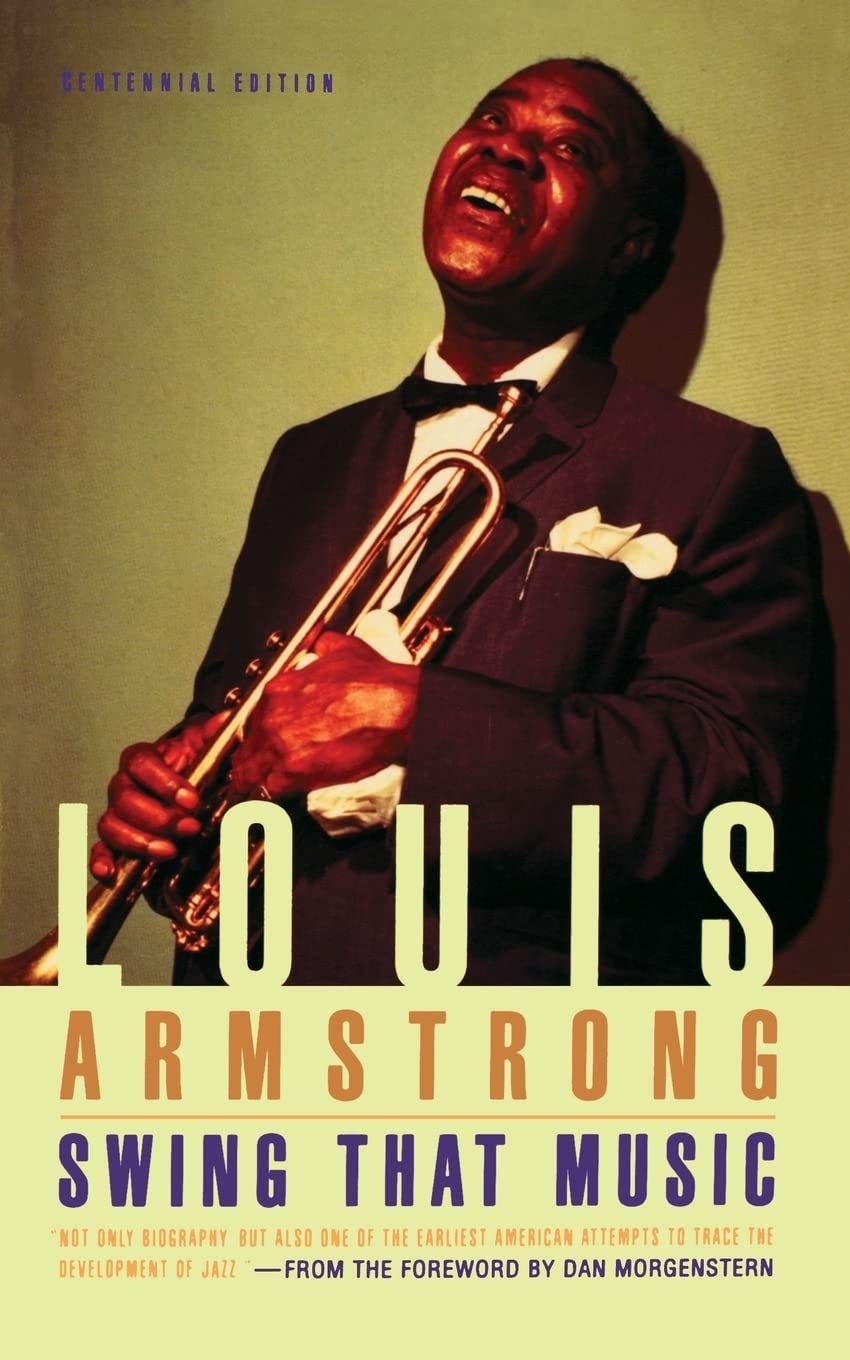

With his career back on track, Armstrong set a number of African American firsts. In 1936, he became the first Black jazz musician to write an autobiography: Swing That Music. That same year, he became the first African American to get featured billing in a major Hollywood movie with his turn in Pennies from Heaven, starring Bing Crosby. Armstrong continued to appear in major movies with the likes of Mae West, Martha Raye, and Dick Powell.

In 1937, Armstrong became the first Black entertainer to host a nationally sponsored radio show when he took over Rudy Vallee’s Fleischmann’s Yeast Show for 12 weeks. He was a frequent presence on radio and often broke box-office records at the height of what is now known as the Swing Era.

Louis Armstrong and the All Stars

By the mid-’40s, the Swing Era was winding down, and the era of big bands was almost over. Seeing the writing on the wall, Armstrong scaled down to a smaller six-piece combo, the All Stars, who he performed live with until the end of his career. Personnel frequently changed. Members of the group, at one time or another, included Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines, Sid Catlett, Barney Bigard, Trummy Young, Edmond Hall, Billy Kyle, and Tyree Glenn, among other jazz legends.

Armstrong continued recording for Decca in the late 1940s and early ’50s, creating a string of popular hits, including “Blueberry Hill,” “That Lucky Old Sun,” “A Kiss to Build a Dream On,” and “I Get Ideas.”

Armstrong signed with Columbia Records in the mid-’50s and soon cut some of the finest albums of his career for producer George Avakian, including Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy and Satch Plays Fats.

Wives

Armstrong wed four times, the first during his teen years. In 1918, he married Daisy Parker, a sex worker. That commenced a stormy union marked by many arguments and acts of violence that ultimately ended in 1923.

During his first marriage, Armstrong adopted a 3-year-old boy named Clarence. The boy’s mother was Armstrong’s cousin who had died in childbirth. Clarence suffered a head injury at a young age and was mentally disabled for the rest of his life.

Armstrong’s second wife was a fellow musician. Shortly after joining the Creole Jazz Band in Chicago, he started dating the female pianist in the group, Lillian Hardin. They married in 1924 but separated seven years later.

During his marriage to Hardin, Armstrong began a relationship with a young dancer named Alpha Smith. In 1938, Armstrong finally divorced Hardin and married Smith, whom he had been dating for more than a decade. Their marriage was not a happy one, however, and they divorced in 1942.

That same year, Armstrong married for the fourth and final time. He wed Lucille Wilson, a Cotton Club dancer. They remained married until his death in 1971.

Alleged Daughter Sharon Preston-Folta

Armstrong’s four marriages never produced any biological children. Because he and his wife Lucille had actively tried for years to no avail, many believe him to be incapable of having children.

However, controversy regarding Armstrong’s fatherhood struck in 1954, when a girlfriend that the musician had dated on the side named Lucille “Sweets” Preston claimed she was pregnant with his child. Preston gave birth to a daughter, Sharon Preston, in 1955.

Shortly thereafter, Armstrong bragged about the child to his manager Joe Glaser in a letter that was later published in the book Louis Armstrong In His Own Words (1999). Thereafter until his death in 1971, however, Armstrong never publicly addressed whether he was Sharon’s father.

Armstrong’s alleged daughter, who now goes by the name Sharon Preston-Folta, has publicized various letters between her and her father. The letters, dated as far back as 1968, prove that Armstrong had always believed Sharon to be his daughter and that he even paid for her education and home, among several other things, throughout his life. Perhaps most importantly, the letters also detail Armstrong’s fatherly love for Sharon.

In December 2012, Preston-Folta published the memoir Little Satchmo: Living in the Shadow of My Father, Louis Daniel Armstrong, about her relationship and connection with the famous musician.

A DNA test could officially prove whether a blood relationship does exist between Armstrong and Preston-Folta, but if one has been conducted, it hasn’t been publicly shared. However, believers and skeptics can at least agree on one thing: Sharon’s uncanny resemblance to the jazz legend.

Ambassador Satch

When Armstrong’s popularity overseas skyrocketed, it led some to alter his longtime nickname “Satchmo” to “Ambassador Satch.” He performed all over the world in the 1950s and ’60s, including throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia. Legendary CBS newsman Edward R. Murrow followed Armstrong with a camera crew on some of his worldwide excursions, turning the resulting footage into a theatrical documentary, Satchmo the Great, released in 1957.

Although his popularity was hitting new highs in the 1950s, and despite breaking down so many barriers for his race, making him a hero in the Black community, Armstrong began to lose standing with two segments of his audience: modern jazz fans and young African Americans.

Bebop, a new form of jazz, had blossomed in the 1940s. Featuring young geniuses such as Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and Miles Davis, the younger generation of musicians saw themselves as artists, not as entertainers. They saw Armstrong’s stage persona and music as old-fashioned and criticized him in the press. Armstrong fought back, but for many young jazz fans, he was regarded as an out-of-date performer with his best days behind him.

The Civil Rights Movement was growing stronger with each passing year, with more protests, marches, and speeches from Black Americans wanting equal rights. To many young jazz listeners at the time, Armstrong’s ever-smiling demeanor seemed like it was from a bygone era. The trumpeter’s refusal to comment on politics for many years only furthered perceptions that he was out of touch.

Support of the Little Rock Nine

Armstrong’s previous silence on racial issues changed in 1957, when the musician saw the Little Rock Central High School integration crisis on television. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus sent in the National Guard to prevent the Little Rock Nine, a group of nine African American students, from entering the public school.

When Armstrong saw this, as well as white protesters hurling invective at the students, he blew his top to the press, telling a reporter that President Dwight D. Eisenhower had “no guts” for letting Faubus run the country. “The way they are treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell,” Armstrong said.

His words made front-page news around the world. Although he had finally spoken out after years of remaining publicly silent, he received criticism at the time from both Black and white public figures. Not a single jazz musician who had previously criticized him took his side, but today, this is seen as one of the bravest, most definitive moments of Armstrong’s life.

Later Career: “Hello, Dolly!” and More International Tours

Armstrong continued a grueling touring schedule into the late ’50s, and it caught up with him in 1959 when he had a heart attack while traveling in Spoleto, Italy. The musician didn’t let the incident stop him, however. After taking a few weeks off to recover, he was back on the road, performing 300 nights a year into the 1960s.

Armstrong was still a popular attraction around the world in 1963 but hadn’t made a record in two years. That December, he was called into the studio to record the title number for a Broadway show that hadn’t opened yet, Hello, Dolly!

The record “Hello, Dolly!” was released in 1964 and quickly climbed to the top of the Billboard Hot 100, hitting the No. 1 slot in May 1964. The chart-topper even dethroned The Beatles at the height of Beatlemania. It also earned Armstrong his only Grammy Award for Best Male Vocal Performance.

This newfound popularity introduced Armstrong to a new, younger audience, and he continued making both successful records and concert appearances for the rest of the decade, even cracking the Iron Curtain with a tour of Communist countries such as East Berlin and Czechoslovakia in 1965.

By 1968, Armstrong’s grueling lifestyle had finally caught up with him. Heart and kidney problems forced him to stop performing in 1969. That same year, his longtime manager, Joe Glaser, died. Armstrong spent much of that year at home but managed to continue practicing the trumpet daily.

Armstrong restarted his public performances by the summer of 1970. After a successful engagement in Las Vegas, Armstrong began taking engagements around the world once more, including in London; Washington, D.C.; and New York City, where he performed for two weeks at the Waldorf-Astoria.

Two days after the Waldorf gig, Armstrong had a heart attack that sidelined him for two months. He returned home in May 1971, though he soon resumed playing again. He promised to perform in public once more, but it was a promise he couldn’t keep.

When Did Louis Armstrong Die?

Armstrong he died in his sleep on July 6, 1971, at his home in the Queens borough of New York City. He was a month shy of his 70th birthday.

Since his death, Armstrong’s stature has only continued to grow. His Queens home at 34-56 107th Street in Corona, New York was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1977. He and his wife Lucille moved into the home in 1943 after she convinced him to purchase a house. Today, the building is home to the Louis Armstrong House Museum, which annually receives thousands of visitors from all over the world.

In the 1980s and ’90s, younger Black jazz musicians like Wynton Marsalis, Jon Faddis, and Nicholas Payton began speaking about Armstrong’s importance, both as a musician and a human being.

A series of biographies on Armstrong made his role as a civil rights pioneer abundantly clear and, subsequently, argued for an embrace of his entire career’s output, not just the revolutionary recordings from the 1920s.

Louis Armstrong Stadium, part of the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center that annually hosts the U.S. Open in New York City, is named in his honor.

Quotes

- The memory of things gone is important to a jazz musician.

- If you have to ask what jazz is, you’ll never know.

- All music is folk music. I ain’t never heard a horse sing a song.

- The colors of the rainbow, so pretty in the sky, are also on the faces of people going by.

- The bright blessed day, the dark sacred night. I think to myself, what a wonderful world.

- Seems to me it ain’t the world that’s so bad but what we’re doing to it, and all I’m saying is: see what a wonderful world it would be if only we’d give it a chance. Love, baby—love. That’s the secret.

- We all do “do re mi,” but you have got to find the other notes yourself.

- Making money ain’t nothing exciting to me. You might be able to buy a little better booze than the wino on the corner. But you get sick just like the next cat, and when you die, you’re just as graveyard dead as he is.

- What we play is life.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.